At the recent Safer Internet Forum, Julie Inman Grant, Australia’s eSafety Commissioner, delivered a keynote titled “Why age matters?”. This article, based on that keynote, provides a comprehensive overview of the Australian online safety framework, including the recently adopted social media delay for children under the age of 16.

From Canberra to Brussels, and beyond, we are grappling with similar questions when it comes to child online safety: What does a healthy digital childhood look like? Where do we draw boundaries? How do we design platforms and rules that nudge the internet toward care, not harm?

“There is so much that unites us rather than divides us in how young people and policymakers around the world think about online safety.”

Australia’s approach centres on a landmark law often referred to as a social media age restriction bill, more commonly referred to as a 'social media delay.' Rather than an absolute prohibition, the law raises the minimum age for holding a social media account from 13 to 16, creating a window in which children can build digital literacy, critical reasoning, and resilience before entering the more complex and persuasive environments of social platforms. It’s a focused intervention with clear goals: limit exposure to harmful content, reduce grooming and harassment, and give families time and leverage to shape healthier digital habits. But this age threshold is not a standalone fix. It sits within a decade-long evolution of Australia’s eSafety framework, a model of prevention, protection, and partnership that seeks to keep all Australians safer online.

In 2015, Australia’s eSafety Commissioner was launched as a pragmatic solution to urgent harms: a hotline for reports of child sexual abuse material and terrorist content online, and the first dedicated cyberbullying takedown scheme for young people. When a child was threatened, harassed, or humiliated online, families and schools could contact the eSafety Commissioner; it intervened directly with platforms to remove the content swiftly, knowing that speed is often the difference between an incident and an enduring trauma.

Over time, and due to the Commissioner's successes, its remit expanded. In 2021, the Australian government introduced an adult cyber abuse scheme to address high-end harms, such as cyberstalking, doxxing, direct threats of sexual violence or death. Today, it receives around 80,000 reports a year from a population of 26 million. Correspondingly, it achieves roughly a 98 per cent success rate in removals for the most acute categories, including image-based abuse and deepfakes. Those numbers tell two stories: online abuse is pervasive, and rapid, reliable remediation matters.

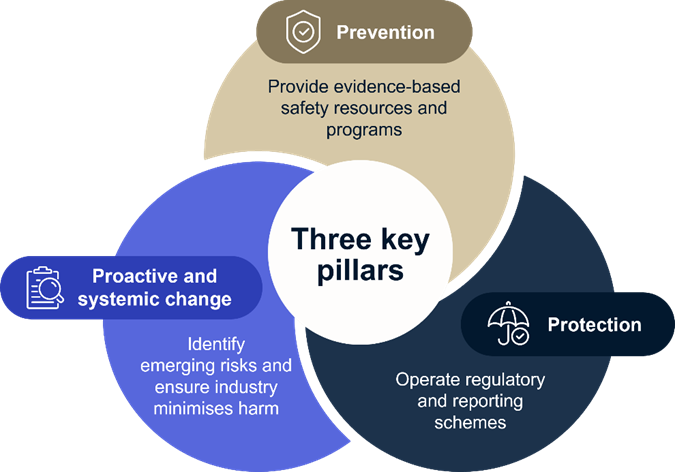

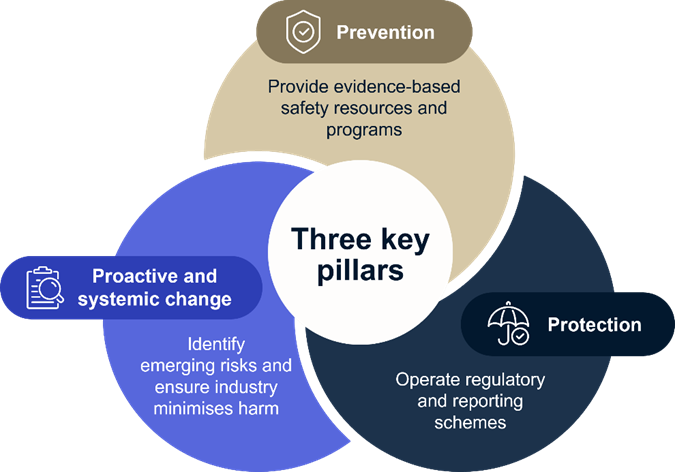

The eSafety Commissioner's operating model: Prevention, protection and proactive and systemic change

The eSafety Commissioner has developed an operating model to guide its practices, referred to as the 3 Ps model:

- Prevention: Evidence-based safety resources, programmes, curricula, and capacity-building materials designed to stop harm before it starts.

Resources and capacity-building materials are developed with young people, not for them. "Nothing about us without us” is more than a motto; it is a method. Children as young as two are touching screens. By the age of four, large numbers already have access to devices. That early exposure demands age-appropriate education that grows with the child, from the pre-school years through primary and secondary school to adulthood. Older Australians are not forgotten either. They are often underrepresented online but are disproportionately vulnerable to scams and social engineering. They need tailored support, too. - Protection: Complaint handling, investigations, and regulatory schemes that remove abusive content and hold platforms accountable.

Systemic powers for transparency exist in Australia, similar to those in the European Digital Services Act (DSA). Equally, codes and standards regulate eight sectors of the tech industry, from device manufacturers to search engines, internet service providers, social networks, and beyond. Complaint schemes are in place, taking reports from the public when there is child cyberbullying or image-based abuse, such as the non-consensual sharing of intimate images and videos, including deepfakes. These frameworks recognise that safety is not just about what happens on a single app; it’s about how an entire tech stack can either mitigate harm or multiply it. - Proactive and systemic change: Through systemic powers and promotion of 'safety by design', in addition to protection through Australia’s unique and world-leading complaint schemes and prevention through online safety resources, education, and research.

Underpinning these three core Ps is a fourth, partnerships. This allows collaboration across government, law enforcement and community organisations, and sharing of best practices with fellow regulators around the globe, promoting international regulatory coherence.

The 3 Ps model

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

The Unlawful Material and Age-Restricted Material Codes and Standards

A significant part of the eSafety Commissioner’s work, which is enshrined in the Australian Unlawful Material Codes and Standards, is ensuring that illegal content, for example, classified violent material, child sexual exploitation material, terror and violence content, does not circulate. The Age-Restricted Material Codes cover another part of these efforts, and regulatory guidance was released in December 2025. These Codes require a broad array of online services to focus on harmful content categories (pornography, explicit violence, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and disordered-eating content) that may not always be illegal, but are profoundly unsafe for minors.

Measures include requiring search engines to blur automatically, for instance, violent or pornographic content by default, applying intermediary warnings, and making sensitive content labels meaningful. Adults who actively wish to proceed can click through, but the baseline is protection.

Why start with the search engines? Because for many young people, search is the gateway, not the destination. Children report encountering explicit material accidentally while searching for something else. That 'in-your-face', unsolicited exposure can be shocking, confusing, and in some cases, traumatising. Adding friction is a simple, scalable way to reduce accidental harm without resorting to intrusive age checks for every search query.

It has been seen how the absence of automated protection mechanisms, such as blurring, plays out when violent content spreads unchecked. It normalises cruelty, desensitises viewers, and, particularly among adolescents, can contribute to radicalisation. The internet’s velocity turns a violent incident into a spectacle. Design choices, such as auto-play and endless scroll, turn the spectacle into a stream. The aim is to reduce the likelihood that a child stumbles into that stream and gets pulled under.

Safety by design: The tech industry’s 'seatbelt moment'

Decades ago, carmakers resisted seatbelts. Today, they compete on safety. One belief is that the tech industry is overdue for its own 'seatbelt moment'. Safety by design must be embedded up front, not retrofitted after harm, and that is why it is also so important that safety by design builds the foundation of initiatives like the DSA.

Safety by design means assessing risks at the concept stage, not patching holes post-launch. It means designing with the most vulnerable users in mind and placing guardrails where features are most likely to fail.

"Platforms should embed safety at the beginning rather than retrofitting after the damage has been done."

We are beginning to see movement. Some major platforms, including online messaging, social, and dating companies, have established safety-by-design divisions. This is not the finish line. Profit-maximising incentives remain powerful. But it is a start. The point is not to punish innovation; it is to require that innovation account for human safety, as modern cars do for collisions: anticipating the worst so that the worst is less likely.

An international nexus: Coordinating across borders

The internet has no borders, and no online safety regulator can do this work alone. The targets of regulatory work are global platforms with users everywhere and servers anywhere. Enforcement actions in one country can be undermined by inaction elsewhere. That’s why coordinated responses and shared expectations across jurisdictions are important. With the rise of like-minded regulators in the UK, Ireland, Fiji, and elsewhere, a Global Online Safety Regulators Network has been established to coordinate actions, share intelligence, and build common standards.

A vivid example is a recently circulating violent incident that was classified as illegal content in Australia. Most platforms complied with takedown demands. One major platform chose to litigate, framing the issue as an overreach into 'the global internet.' The result was paradoxical: Australians were protected domestically, yet the same content remained available abroad. For young people watching from other countries, the emissions of a single platform became a point of exposure for the world. It is a reminder that online safety is a global public good. Piecemeal compliance is not enough.

Cyberbullying has evolved: Younger victims, harsher language, new weaponised digital tools

In Europe, one of President Ursula von der Leyen's key priorities is combating cyberbullying; a priority which is shared in Australia. The eSafety Commissioner's website provides a rich wealth of materials and resources spotlighting cyberbullying.

Cyberbullying is a phenomenon where age matters ever more. We are seeing younger victims, sometimes children as young as eight or nine, and more corrosive language, aggressive, sexualised, and crafted to isolate. The platforms are not limited to stereotypical social apps. They include platforms not traditionally associated with harm, such as creative boards, form-building tools, and even music streaming.

Consider weaponised music playlists curated to mock a single child with songs whose titles convey cruel messages. Or the use of emojis and acronyms as coded language that slips past adult detection but lands squarely on a child’s psyche. Add deepfake technologies like voice cloning, face swapping, and body-based insults generated through easy-to-use generative artificial intelligence (genAI) tools, and the result is a bullying landscape where a child’s likeness can be manipulated into scenes they never lived, words they never spoke, and actions they never took, and then spread faster than any correction can catch them.

The task here is twofold. One is to equip schools, families, and children with the skills and protocols to respond quickly, and the other is to require platforms to disrupt these modes of abuse within their product ecosystems, through detection, friction, and enforcement.

Deepfakes and AI-based 'de-clothing': A new epidemic and a hard line

One of the ugliest patterns seen is AI deepfake sexual abuse, often targeting schoolgirls. A typical scenario is that a teenage boy harvests images of female classmates and runs them through de-clothing websites, producing synthetic sexual content. Many perpetrators do not grasp the gravity of their actions. They are creating synthetic child sexual abuse material, a criminal act, and inflicting profound humiliation and harm.

Here, a dual strategy has been pursued in Australia: rapid takedowns in individual cases (with a 98 per cent success rate) and systemic enforcement against companies that profit from these tools. Breaches of codes and standards carry maximum civil penalties of up to AU$20,000. Action has been taken against a UK-based 'nudifying' site that powered several of the world’s most common apps. When confronted, they restricted access in Australia, but before that, high website visits were observed. In another case, an Australian man who habitually produced deepfakes of female public figures and sexual violence survivors was taken to court, resulting in a significant penalty. The message to the public is simple yet important: there is no impunity for such acts.

Australian schools voiced that they were unprepared for these incidents and unsure how to respond. Hence, an incident management tool for schools was created to advise them on how to collect evidence, treat perpetrators and victims, communicate, and restore a sense of safety without compounding the harm. The goal is to equip the adults in a child’s environment so that the first responses are timely, calm, and protective.

AI companions and chatbots: Guardrails for the new 'friends'

Anecdotal evidence from Australian schools suggested that students were spending up to five to six hours a day with AI companions, which are chatbots marketed as cures for loneliness. Some went beyond companionship, encouraging sexualised interactions or romantic role-play that spiralled into emotional dependency. Others produced content that promoted self-harm or disordered eating, or failed to step back from suicidal ideation. Alongside cases in Australia, legal actions abroad reflect similar concerns.

The Australian response has been to register codes that prevent AI chatbots and companions from delivering sexual, pornographic, suicidal, or eating-disorder content to minors. This is not a call to dismantle AI’s potential for support or learning. It is a demand that AI systems respect age boundaries and avoid high-risk content with children. As a society, we must not relive the 'move fast and break things' era of social media, this time with AI.

Real-world platform commitments: Progress and pressure

Codes and standards are only as good as their implementation. Some major platforms have committed to protecting children more systematically. For example, a large game-based social environment agreed to prevent adult-to-child direct contact, set high privacy defaults for child accounts, and pursue age verification across its user base. Why? Because when a platform’s fastest-growing segment is adults, and its primary users are children, the consequences of co-mingled spaces without robust safeguards can be dire.

The Australian app store code was used when a video chat app failed to address the issue of predator pairing. De-platforming at the distribution level, that is, removing access for such apps to be distributed via app stores, became the lever that forced change. When platform operators ignore the harm, choke points, such as app stores, matter, because they facilitate that such an app cannot be distributed and monetised.

The Australian social media delay: What it is and what it isn’t

Now to the heart of the currently ongoing child online safety discourse: the Australian social media delay. The delay means raising the minimum age for accounts on certain social media platforms from 13 to 16. It should be referred to as a delay, not a ban or prohibition; the language matters for policy, platforms, and families. Parents shouldn’t have to say 'never'. Instead, they should be able to say 'not yet'. And the law should support that stance by requiring platforms to take reasonable steps to prevent under-16-year-olds from holding accounts, shifting the compliance burden away from parents and children, and onto the companies that profit from youth engagement.

Why a delay? Because social platforms are engineered with persuasive design features, such as endless scroll, auto-play, streaks, and engagement loops, that hook attention and extract time. Adults struggle to resist these forces. Expecting children to do so is unrealistic. The delay buys time; time to grow judgment, time to learn digital literacy, and time for families to build habits that make social media use, when it comes, more deliberate.

The Australian social media delay

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

This approach was developed with young people's digital lifelines in mind. Spaces where marginalised young people, for example, from LGBTQIA+ communities or First Nations Australians, find identity, connection, and support. The intention is not to cut those lifelines; the Australian legislators still want them to be able to 'find their tribe'. That’s why the Minister for Communications has made rules that set out exclusions for messaging and gaming services, and why a holistic approach emphasises building skills and scaffolding rather than erasing sociality altogether.

Findings from Australia’s 2025 eSafety survey with 2,600 children aged 10 to 15 showed that 96 per cent reported having used at least one social media platform,7 in 10 had encountered harmful material, and 1 in 10 had experienced online grooming behaviours from either adults or teenagers that were four to five years older than them.

The 'social media delay' has been reviewed and refined over time, together with the eSafety Commissioner’s youth advisory council, which shaped the legislation significantly. It was implemented in a way that supported the child's best interests and respected their digital rights, ensuring that measures were reasonable, necessary, and proportionate.

How enforcement works: Layered age assurance and longitudinal evaluation

While there won't be any penalties for parents or children who hold social media accounts under 16, there will be penalties for companies. Under the law, age-restricted social media platforms must take reasonable steps to detect and deactivate or remove accounts held by users under 16. They already have the data and tools needed. Many run age-inference technologies that look at behavioural signals, such as login times, social graphs, linguistic patterns, and emoji use. A layered, waterfall approach to age assurance is required, using multiple methods in combination and prioritising privacy-preserving techniques over blunt instruments.

Correspondingly, online service providers have been provided with a self-assessment tool to help them determine whether their service meets the legislative definition of an age-restricted social media platform. The criteria under the law include whether the sole purpose or a significant purpose of their service was to enable online social interaction between two or more users, to allow users to link or interact with other users, to allow users to post material on the service, and any of the materials on the service being accessible to users in Australia. At this stage, the restrictions are likely to apply to Facebook, Instagram, Kick, Snapchat, TikTok, Threads, X, Twitch, Reddit and YouTube, among other platforms. Online gaming and standalone messaging apps are among the services excluded under the Minister’s rules.

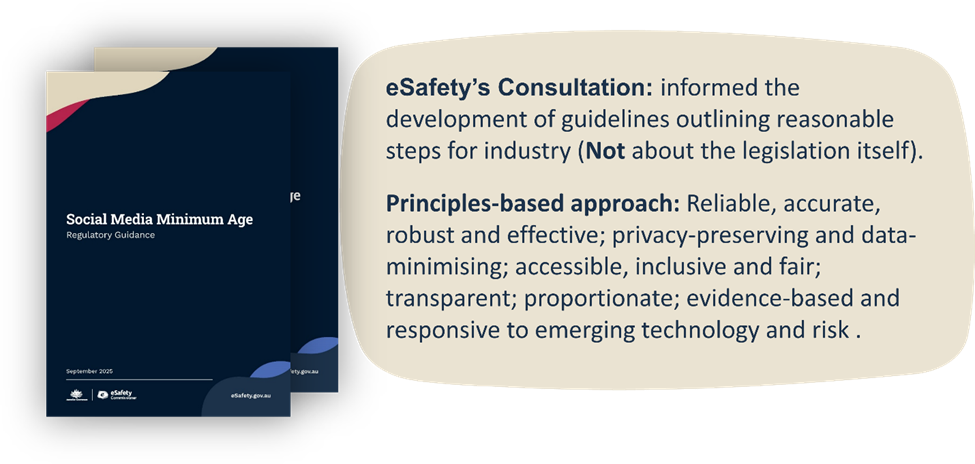

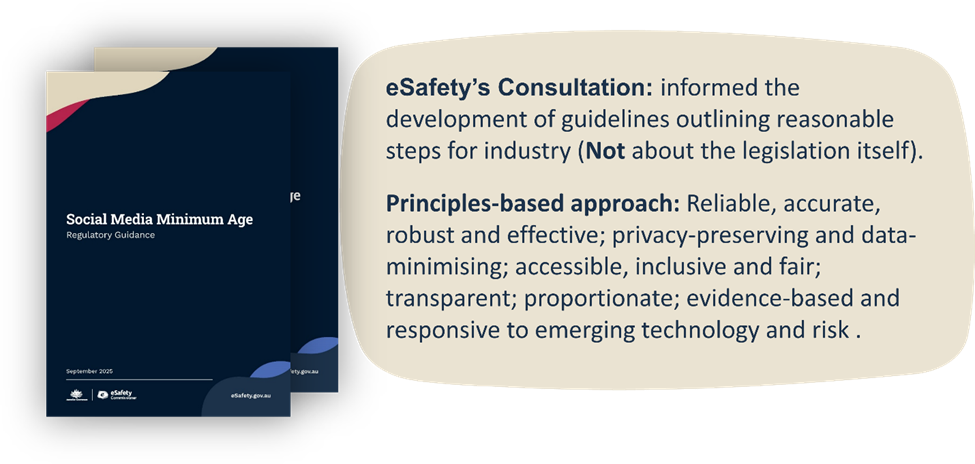

Over 150 organisations, and young people themselves, were consulted, resulting in a principles-based approach to regulatory guidelines for age assurance.

The principles-based approach to age assurance

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

Crucially, platforms are not asked to age-verify the entire user base or force government ID uploads for everyone, and the law specifically prohibits platforms from relying exclusively on government ID. Nor was a single winning technology prescribed. Instead, the results of the Australian Government-sponsored Age Assurance Technical Trial were considered, which tested around 50 tools, from facial age estimation to parental consent and multi-factor validation. Many robust, accurate, and privacy-respecting options were found. When companies try to claim that a specific technology is immature, they are directed to the evidence: third-party solutions exist, and they work.

Implementation demands care. Platforms must communicate transparently and with kindness, and give notice before removing underage accounts. They must also address underage users re-registering through layered checks and iterative improvement. They should assess efficacy, over-blocking and under-blocking, and show how they’re calibrating systems over time. It is recognised that some slips will occur; that’s why appeals and remedies are integral. The goal is not perfection; it is continuous improvement and documented diligence.

Australia is also watching what is happening around the world, including, for instance, the UK age assurance, and anticipates migratory patterns and surges in VPN use and other forms of circumvention. Correspondingly, platforms are expected to monitor for signals that may indicate potential circumvention, which may then trigger an age assurance process.

eSafety's clear expectations from online service providers

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

It is also believed that policy should be grounded in evidence, and hence the eSafety Commissioner is conducting an extensive longitudinal evaluation of this legislation to assess its implementation and impact on young people, including both benefits and unintended consequences. In doing so, the implementation of the social media minimum age will be monitored, with the aim of understanding the short- and long-term impacts, providing evidence to inform an independent review of the implementation, and contributing to the evidence base on the relationship between social media and youth well-being. For that purpose, an academic advisory group has been formed, with specialists from Australia and around the world, with strong expertise at the intersection of youth mental health and technology. The advisory group will explore a variety of factors, from kids' sleep to changes in social interactions and participation in sports and activities, such as reading, to statistics on medication intake, such as antidepressant use, and family expenses for children's phone bills, changes in school test scores, and so on. As can be seen, it’s a very comprehensive set of indicators that aims to provide a holistic understanding of the impacts of this legislation. In addition, unintended consequences will be examined to critically reflect on whether 16 was indeed the right age, or whether it should be changed to 15 or 18. All this wealth of data and evidence will be made available to other countries as well, fostering mutual learning from successes and mistakes.

A call to collective action

Online safety is a shared responsibility. Regulators must be forward-looking and firm. Platforms must embed safety by design. Parents and schools must guide and support. And young people must continue to shape the agenda. We have seen that when youth advisory councils testify before parliament, draft submissions, and co-design materials, policy becomes more humane and effective.

To that end, the eSafety Commissioner's website makes available a wide range of support and resources on the eSafety social media age restriction hub. It is a one-stop shop that provides the most up-to-date information and resources for parents and carers, young people, educators, and online service providers.

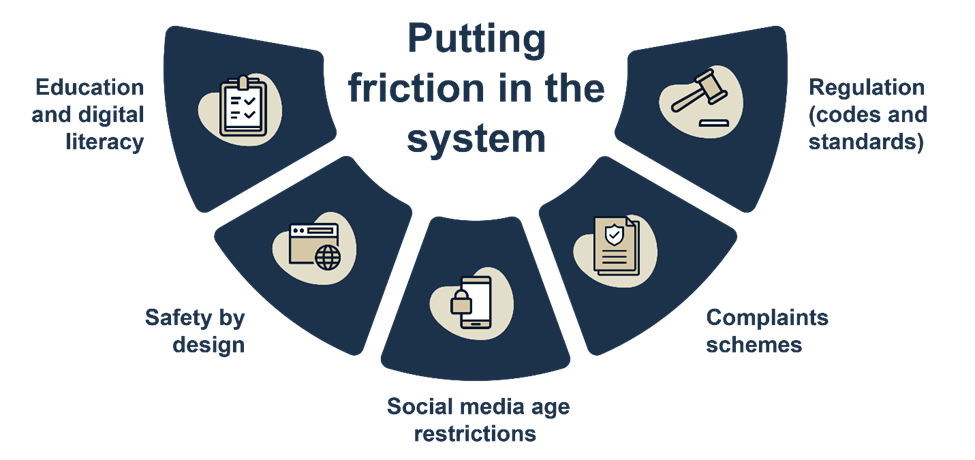

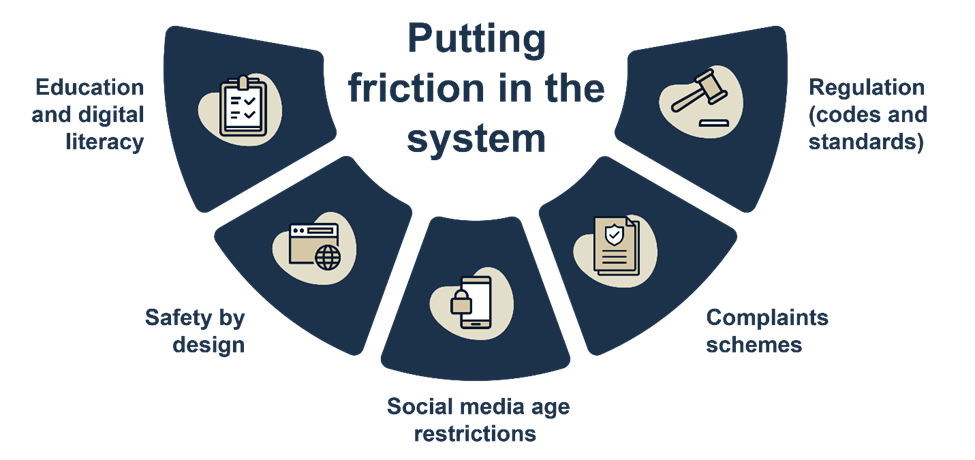

Putting friction in the systems

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

This article is based on a keynote address by the Australian eSafety Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, delivered at the 2025 Safer Internet Forum in Brussels. Listen to the full keynote, and other session recordings from the event, on the Better Internet for Kids YouTube channel.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Better Internet for Kids or the European Commission.

Interested in more?

If you are interested in more policy insight, explore the BIK Knowledge hub, including the BIK Policy monitor, the Rules and guidelines and Research and reports directories, where we draw together relevant policy instruments, reports and research informing the implementation of the BIK+ strategy at the national level.

Find more BIK Knowledge hub insights articles here.

Finally, don't forget to read the BIK Age assurance guide on our platform for more information on how different methods of age assurance work.

At the recent Safer Internet Forum, Julie Inman Grant, Australia’s eSafety Commissioner, delivered a keynote titled “Why age matters?”. This article, based on that keynote, provides a comprehensive overview of the Australian online safety framework, including the recently adopted social media delay for children under the age of 16.

From Canberra to Brussels, and beyond, we are grappling with similar questions when it comes to child online safety: What does a healthy digital childhood look like? Where do we draw boundaries? How do we design platforms and rules that nudge the internet toward care, not harm?

“There is so much that unites us rather than divides us in how young people and policymakers around the world think about online safety.”

Australia’s approach centres on a landmark law often referred to as a social media age restriction bill, more commonly referred to as a 'social media delay.' Rather than an absolute prohibition, the law raises the minimum age for holding a social media account from 13 to 16, creating a window in which children can build digital literacy, critical reasoning, and resilience before entering the more complex and persuasive environments of social platforms. It’s a focused intervention with clear goals: limit exposure to harmful content, reduce grooming and harassment, and give families time and leverage to shape healthier digital habits. But this age threshold is not a standalone fix. It sits within a decade-long evolution of Australia’s eSafety framework, a model of prevention, protection, and partnership that seeks to keep all Australians safer online.

In 2015, Australia’s eSafety Commissioner was launched as a pragmatic solution to urgent harms: a hotline for reports of child sexual abuse material and terrorist content online, and the first dedicated cyberbullying takedown scheme for young people. When a child was threatened, harassed, or humiliated online, families and schools could contact the eSafety Commissioner; it intervened directly with platforms to remove the content swiftly, knowing that speed is often the difference between an incident and an enduring trauma.

Over time, and due to the Commissioner's successes, its remit expanded. In 2021, the Australian government introduced an adult cyber abuse scheme to address high-end harms, such as cyberstalking, doxxing, direct threats of sexual violence or death. Today, it receives around 80,000 reports a year from a population of 26 million. Correspondingly, it achieves roughly a 98 per cent success rate in removals for the most acute categories, including image-based abuse and deepfakes. Those numbers tell two stories: online abuse is pervasive, and rapid, reliable remediation matters.

The eSafety Commissioner's operating model: Prevention, protection and proactive and systemic change

The eSafety Commissioner has developed an operating model to guide its practices, referred to as the 3 Ps model:

- Prevention: Evidence-based safety resources, programmes, curricula, and capacity-building materials designed to stop harm before it starts.

Resources and capacity-building materials are developed with young people, not for them. "Nothing about us without us” is more than a motto; it is a method. Children as young as two are touching screens. By the age of four, large numbers already have access to devices. That early exposure demands age-appropriate education that grows with the child, from the pre-school years through primary and secondary school to adulthood. Older Australians are not forgotten either. They are often underrepresented online but are disproportionately vulnerable to scams and social engineering. They need tailored support, too. - Protection: Complaint handling, investigations, and regulatory schemes that remove abusive content and hold platforms accountable.

Systemic powers for transparency exist in Australia, similar to those in the European Digital Services Act (DSA). Equally, codes and standards regulate eight sectors of the tech industry, from device manufacturers to search engines, internet service providers, social networks, and beyond. Complaint schemes are in place, taking reports from the public when there is child cyberbullying or image-based abuse, such as the non-consensual sharing of intimate images and videos, including deepfakes. These frameworks recognise that safety is not just about what happens on a single app; it’s about how an entire tech stack can either mitigate harm or multiply it. - Proactive and systemic change: Through systemic powers and promotion of 'safety by design', in addition to protection through Australia’s unique and world-leading complaint schemes and prevention through online safety resources, education, and research.

Underpinning these three core Ps is a fourth, partnerships. This allows collaboration across government, law enforcement and community organisations, and sharing of best practices with fellow regulators around the globe, promoting international regulatory coherence.

The 3 Ps model

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

The Unlawful Material and Age-Restricted Material Codes and Standards

A significant part of the eSafety Commissioner’s work, which is enshrined in the Australian Unlawful Material Codes and Standards, is ensuring that illegal content, for example, classified violent material, child sexual exploitation material, terror and violence content, does not circulate. The Age-Restricted Material Codes cover another part of these efforts, and regulatory guidance was released in December 2025. These Codes require a broad array of online services to focus on harmful content categories (pornography, explicit violence, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and disordered-eating content) that may not always be illegal, but are profoundly unsafe for minors.

Measures include requiring search engines to blur automatically, for instance, violent or pornographic content by default, applying intermediary warnings, and making sensitive content labels meaningful. Adults who actively wish to proceed can click through, but the baseline is protection.

Why start with the search engines? Because for many young people, search is the gateway, not the destination. Children report encountering explicit material accidentally while searching for something else. That 'in-your-face', unsolicited exposure can be shocking, confusing, and in some cases, traumatising. Adding friction is a simple, scalable way to reduce accidental harm without resorting to intrusive age checks for every search query.

It has been seen how the absence of automated protection mechanisms, such as blurring, plays out when violent content spreads unchecked. It normalises cruelty, desensitises viewers, and, particularly among adolescents, can contribute to radicalisation. The internet’s velocity turns a violent incident into a spectacle. Design choices, such as auto-play and endless scroll, turn the spectacle into a stream. The aim is to reduce the likelihood that a child stumbles into that stream and gets pulled under.

Safety by design: The tech industry’s 'seatbelt moment'

Decades ago, carmakers resisted seatbelts. Today, they compete on safety. One belief is that the tech industry is overdue for its own 'seatbelt moment'. Safety by design must be embedded up front, not retrofitted after harm, and that is why it is also so important that safety by design builds the foundation of initiatives like the DSA.

Safety by design means assessing risks at the concept stage, not patching holes post-launch. It means designing with the most vulnerable users in mind and placing guardrails where features are most likely to fail.

"Platforms should embed safety at the beginning rather than retrofitting after the damage has been done."

We are beginning to see movement. Some major platforms, including online messaging, social, and dating companies, have established safety-by-design divisions. This is not the finish line. Profit-maximising incentives remain powerful. But it is a start. The point is not to punish innovation; it is to require that innovation account for human safety, as modern cars do for collisions: anticipating the worst so that the worst is less likely.

An international nexus: Coordinating across borders

The internet has no borders, and no online safety regulator can do this work alone. The targets of regulatory work are global platforms with users everywhere and servers anywhere. Enforcement actions in one country can be undermined by inaction elsewhere. That’s why coordinated responses and shared expectations across jurisdictions are important. With the rise of like-minded regulators in the UK, Ireland, Fiji, and elsewhere, a Global Online Safety Regulators Network has been established to coordinate actions, share intelligence, and build common standards.

A vivid example is a recently circulating violent incident that was classified as illegal content in Australia. Most platforms complied with takedown demands. One major platform chose to litigate, framing the issue as an overreach into 'the global internet.' The result was paradoxical: Australians were protected domestically, yet the same content remained available abroad. For young people watching from other countries, the emissions of a single platform became a point of exposure for the world. It is a reminder that online safety is a global public good. Piecemeal compliance is not enough.

Cyberbullying has evolved: Younger victims, harsher language, new weaponised digital tools

In Europe, one of President Ursula von der Leyen's key priorities is combating cyberbullying; a priority which is shared in Australia. The eSafety Commissioner's website provides a rich wealth of materials and resources spotlighting cyberbullying.

Cyberbullying is a phenomenon where age matters ever more. We are seeing younger victims, sometimes children as young as eight or nine, and more corrosive language, aggressive, sexualised, and crafted to isolate. The platforms are not limited to stereotypical social apps. They include platforms not traditionally associated with harm, such as creative boards, form-building tools, and even music streaming.

Consider weaponised music playlists curated to mock a single child with songs whose titles convey cruel messages. Or the use of emojis and acronyms as coded language that slips past adult detection but lands squarely on a child’s psyche. Add deepfake technologies like voice cloning, face swapping, and body-based insults generated through easy-to-use generative artificial intelligence (genAI) tools, and the result is a bullying landscape where a child’s likeness can be manipulated into scenes they never lived, words they never spoke, and actions they never took, and then spread faster than any correction can catch them.

The task here is twofold. One is to equip schools, families, and children with the skills and protocols to respond quickly, and the other is to require platforms to disrupt these modes of abuse within their product ecosystems, through detection, friction, and enforcement.

Deepfakes and AI-based 'de-clothing': A new epidemic and a hard line

One of the ugliest patterns seen is AI deepfake sexual abuse, often targeting schoolgirls. A typical scenario is that a teenage boy harvests images of female classmates and runs them through de-clothing websites, producing synthetic sexual content. Many perpetrators do not grasp the gravity of their actions. They are creating synthetic child sexual abuse material, a criminal act, and inflicting profound humiliation and harm.

Here, a dual strategy has been pursued in Australia: rapid takedowns in individual cases (with a 98 per cent success rate) and systemic enforcement against companies that profit from these tools. Breaches of codes and standards carry maximum civil penalties of up to AU$20,000. Action has been taken against a UK-based 'nudifying' site that powered several of the world’s most common apps. When confronted, they restricted access in Australia, but before that, high website visits were observed. In another case, an Australian man who habitually produced deepfakes of female public figures and sexual violence survivors was taken to court, resulting in a significant penalty. The message to the public is simple yet important: there is no impunity for such acts.

Australian schools voiced that they were unprepared for these incidents and unsure how to respond. Hence, an incident management tool for schools was created to advise them on how to collect evidence, treat perpetrators and victims, communicate, and restore a sense of safety without compounding the harm. The goal is to equip the adults in a child’s environment so that the first responses are timely, calm, and protective.

AI companions and chatbots: Guardrails for the new 'friends'

Anecdotal evidence from Australian schools suggested that students were spending up to five to six hours a day with AI companions, which are chatbots marketed as cures for loneliness. Some went beyond companionship, encouraging sexualised interactions or romantic role-play that spiralled into emotional dependency. Others produced content that promoted self-harm or disordered eating, or failed to step back from suicidal ideation. Alongside cases in Australia, legal actions abroad reflect similar concerns.

The Australian response has been to register codes that prevent AI chatbots and companions from delivering sexual, pornographic, suicidal, or eating-disorder content to minors. This is not a call to dismantle AI’s potential for support or learning. It is a demand that AI systems respect age boundaries and avoid high-risk content with children. As a society, we must not relive the 'move fast and break things' era of social media, this time with AI.

Real-world platform commitments: Progress and pressure

Codes and standards are only as good as their implementation. Some major platforms have committed to protecting children more systematically. For example, a large game-based social environment agreed to prevent adult-to-child direct contact, set high privacy defaults for child accounts, and pursue age verification across its user base. Why? Because when a platform’s fastest-growing segment is adults, and its primary users are children, the consequences of co-mingled spaces without robust safeguards can be dire.

The Australian app store code was used when a video chat app failed to address the issue of predator pairing. De-platforming at the distribution level, that is, removing access for such apps to be distributed via app stores, became the lever that forced change. When platform operators ignore the harm, choke points, such as app stores, matter, because they facilitate that such an app cannot be distributed and monetised.

The Australian social media delay: What it is and what it isn’t

Now to the heart of the currently ongoing child online safety discourse: the Australian social media delay. The delay means raising the minimum age for accounts on certain social media platforms from 13 to 16. It should be referred to as a delay, not a ban or prohibition; the language matters for policy, platforms, and families. Parents shouldn’t have to say 'never'. Instead, they should be able to say 'not yet'. And the law should support that stance by requiring platforms to take reasonable steps to prevent under-16-year-olds from holding accounts, shifting the compliance burden away from parents and children, and onto the companies that profit from youth engagement.

Why a delay? Because social platforms are engineered with persuasive design features, such as endless scroll, auto-play, streaks, and engagement loops, that hook attention and extract time. Adults struggle to resist these forces. Expecting children to do so is unrealistic. The delay buys time; time to grow judgment, time to learn digital literacy, and time for families to build habits that make social media use, when it comes, more deliberate.

The Australian social media delay

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

This approach was developed with young people's digital lifelines in mind. Spaces where marginalised young people, for example, from LGBTQIA+ communities or First Nations Australians, find identity, connection, and support. The intention is not to cut those lifelines; the Australian legislators still want them to be able to 'find their tribe'. That’s why the Minister for Communications has made rules that set out exclusions for messaging and gaming services, and why a holistic approach emphasises building skills and scaffolding rather than erasing sociality altogether.

Findings from Australia’s 2025 eSafety survey with 2,600 children aged 10 to 15 showed that 96 per cent reported having used at least one social media platform,7 in 10 had encountered harmful material, and 1 in 10 had experienced online grooming behaviours from either adults or teenagers that were four to five years older than them.

The 'social media delay' has been reviewed and refined over time, together with the eSafety Commissioner’s youth advisory council, which shaped the legislation significantly. It was implemented in a way that supported the child's best interests and respected their digital rights, ensuring that measures were reasonable, necessary, and proportionate.

How enforcement works: Layered age assurance and longitudinal evaluation

While there won't be any penalties for parents or children who hold social media accounts under 16, there will be penalties for companies. Under the law, age-restricted social media platforms must take reasonable steps to detect and deactivate or remove accounts held by users under 16. They already have the data and tools needed. Many run age-inference technologies that look at behavioural signals, such as login times, social graphs, linguistic patterns, and emoji use. A layered, waterfall approach to age assurance is required, using multiple methods in combination and prioritising privacy-preserving techniques over blunt instruments.

Correspondingly, online service providers have been provided with a self-assessment tool to help them determine whether their service meets the legislative definition of an age-restricted social media platform. The criteria under the law include whether the sole purpose or a significant purpose of their service was to enable online social interaction between two or more users, to allow users to link or interact with other users, to allow users to post material on the service, and any of the materials on the service being accessible to users in Australia. At this stage, the restrictions are likely to apply to Facebook, Instagram, Kick, Snapchat, TikTok, Threads, X, Twitch, Reddit and YouTube, among other platforms. Online gaming and standalone messaging apps are among the services excluded under the Minister’s rules.

Over 150 organisations, and young people themselves, were consulted, resulting in a principles-based approach to regulatory guidelines for age assurance.

The principles-based approach to age assurance

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

Crucially, platforms are not asked to age-verify the entire user base or force government ID uploads for everyone, and the law specifically prohibits platforms from relying exclusively on government ID. Nor was a single winning technology prescribed. Instead, the results of the Australian Government-sponsored Age Assurance Technical Trial were considered, which tested around 50 tools, from facial age estimation to parental consent and multi-factor validation. Many robust, accurate, and privacy-respecting options were found. When companies try to claim that a specific technology is immature, they are directed to the evidence: third-party solutions exist, and they work.

Implementation demands care. Platforms must communicate transparently and with kindness, and give notice before removing underage accounts. They must also address underage users re-registering through layered checks and iterative improvement. They should assess efficacy, over-blocking and under-blocking, and show how they’re calibrating systems over time. It is recognised that some slips will occur; that’s why appeals and remedies are integral. The goal is not perfection; it is continuous improvement and documented diligence.

Australia is also watching what is happening around the world, including, for instance, the UK age assurance, and anticipates migratory patterns and surges in VPN use and other forms of circumvention. Correspondingly, platforms are expected to monitor for signals that may indicate potential circumvention, which may then trigger an age assurance process.

eSafety's clear expectations from online service providers

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

It is also believed that policy should be grounded in evidence, and hence the eSafety Commissioner is conducting an extensive longitudinal evaluation of this legislation to assess its implementation and impact on young people, including both benefits and unintended consequences. In doing so, the implementation of the social media minimum age will be monitored, with the aim of understanding the short- and long-term impacts, providing evidence to inform an independent review of the implementation, and contributing to the evidence base on the relationship between social media and youth well-being. For that purpose, an academic advisory group has been formed, with specialists from Australia and around the world, with strong expertise at the intersection of youth mental health and technology. The advisory group will explore a variety of factors, from kids' sleep to changes in social interactions and participation in sports and activities, such as reading, to statistics on medication intake, such as antidepressant use, and family expenses for children's phone bills, changes in school test scores, and so on. As can be seen, it’s a very comprehensive set of indicators that aims to provide a holistic understanding of the impacts of this legislation. In addition, unintended consequences will be examined to critically reflect on whether 16 was indeed the right age, or whether it should be changed to 15 or 18. All this wealth of data and evidence will be made available to other countries as well, fostering mutual learning from successes and mistakes.

A call to collective action

Online safety is a shared responsibility. Regulators must be forward-looking and firm. Platforms must embed safety by design. Parents and schools must guide and support. And young people must continue to shape the agenda. We have seen that when youth advisory councils testify before parliament, draft submissions, and co-design materials, policy becomes more humane and effective.

To that end, the eSafety Commissioner's website makes available a wide range of support and resources on the eSafety social media age restriction hub. It is a one-stop shop that provides the most up-to-date information and resources for parents and carers, young people, educators, and online service providers.

Putting friction in the systems

© Australian eSafety Commissioner

This article is based on a keynote address by the Australian eSafety Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, delivered at the 2025 Safer Internet Forum in Brussels. Listen to the full keynote, and other session recordings from the event, on the Better Internet for Kids YouTube channel.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Better Internet for Kids or the European Commission.

Interested in more?

If you are interested in more policy insight, explore the BIK Knowledge hub, including the BIK Policy monitor, the Rules and guidelines and Research and reports directories, where we draw together relevant policy instruments, reports and research informing the implementation of the BIK+ strategy at the national level.

Find more BIK Knowledge hub insights articles here.

Finally, don't forget to read the BIK Age assurance guide on our platform for more information on how different methods of age assurance work.

- < Previous article

- Next article >