All over the world, child welfare organisations are working to protect girls and boys from sexualised violence in real life, and also on the internet. However, the sexual exploitation of girls and boys rests on traditions stretching over centuries, and it was not until the 1990s that pedagogical prevention efforts were undertaken and began raising awareness in kindergartens, schools, counselling services and youth authorities towards providing timely support to children and adolescents (Enders, 1990, p. 11).

Nowadays, it is no longer an exception to encounter depictions of abuse, harassment, and cybergrooming on the internetnet. The anonymity in the online world enables adults in disguise to establish contacts with children, to elicit information about sexual matters, and in the worst case, to pave the way for abuse in real life.

The study Online Experience of 9-to-17-Year-Olds conducted by EU Kids Online in 2019 (Hasebrink, Lampert, & Thiel, 2019) revealed that in Germany, 34 per cent of the girls surveyed and 23 per cent of the boys surveyed had been confronted online with intimate or suggestive questions that they did not want to answer. The topical spectrum ranges from questions about sexual experience and preferences to explicit prompting of sexual acts. Older kids seem to be targeted much more frequently, with an occurrence of 15 per cent among 12-to-14-year-olds rising to 43 per cent in the 15-to-17 age group.

With regards to the frequency of grooming, it seems to occur here and there: about one quarter of those surveyed reported occasional attempts they had been confronted with. Among them, one in five said that, during the past year, they had experienced it at least once a month (ibid., p. 25).

The sexual harassment of children and adolescents takes place predominantly on platforms that also address adults and that, in addition to their public areas, offer private communication functions as found in social media and online games. Many of these services are inadequately moderated, and their pre-installed settings do not provide sufficient protection for users. As a result, the risks are especially high (jugendschutz.net, 2019, p. 12).

Statistics from the 30 helplines cooperating in the European network Insafe show a slight increase in inquiries related to the topic of cybergrooming for the years 2018 und 2019 (data provided by the telephone helpline Nummer gegen Kummer). It can be assumed that girls and boys have increasing difficulty in dealing with advances made to them via cybergrooming, and that they therefore seek support.

About 6 per cent of 6-to-7-year-olds in Germany already have their own smartphone. In the 8-to-9-year-old age group, this rises to 33 per cent, and for the 10-to-11 year-olds, it reaches 75 per cent. Among the 12-to-13-year-olds, the proportion of smartphone owners already lies at 95 per cent (Tenzer, 2020, in a study for Bitkom Research Germany). Intelligent mobile phones have become, for many, an essential part of everyday life. Using them brings the popular social media services and communication platforms directly into the lives of children and adolescents.

Practical media education work by the authors with parents, children, and adolescents has shown that very few children and adolescents possess the knowledge necessary for dealing with harassment and sexualised advances. Moreover, younger children in particular are moving about on social media without sufficient technical protection. Many of the popular services are oriented towards interaction and offer options to establish contact – including contact to users who are minors.

All this makes it imperative for children and adolescents to be prepared early for the risks that their use of communication services and social media is very likely to entail. They need to be taught how they can protect themselves from risky contacts and how to react when unpleasant encounters do occur. Prevention implies assuming a position oriented to resources, and emphasising behaviour aimed at resolving conflicts and strategies to protect oneself and others. The focus lies on information, empowerment, and support for children and adolescents. They need information on the risks of the internet and the questionability of posting personal information and images. Once something is on the internet, it becomes very difficult to delete.

The significance of social media for cybergrooming

Young people use the internet preferentially for communication, exchanging or sharing news, photos, or videos with others (mpfs, 2018, p. 34). This makes messenger services and social networks such as WhatsApp, Instagram und Snapchat particularly popular among young users (ibid., p. 39). The app TikTok, which has become known as a playback app, has also gained a following in Germany in recent years particularly among younger girls, and has generated a rash of negative headlines due to cybergrooming cases (Pöting, 2018; jugendschutz.net, 2020). Although social media are used by adolescents primarily for contacts within their own circles, there is nonetheless the possibility that outsiders will use these services to establish contact, or that the young people themselves will cultivate contacts to persons they only know on the net. Outsiders can make contact particularly easily through social media and online games – such as Minecraft or Clash of Clans – that present interactive options: comments, chats, or the like.

Consequently, potential abusers create accounts on social media for the purpose of initiating sexualized relationships (Tagesspiegel, 2019; Giertz, Hautz, Link, & Wahl, 2019, p. 12-13). One typical tactic taken by cybergroomers – persons deliberately contacting minors via social media in order to make sexual advances – is to initiate contact by commenting on content that has been posted on a publicly accessible profile. This means that they begin an exchange in an open chat with the aim of proceeding to a private conversation, for example by shifting to the “direct” function on Instagram.

Platform providers do in fact set an age minimum for users, but they do not enforce it. As a result, there are elementary school children using apps whose terms and conditions stipulate 13 as a minimum age. It follows that, for these youngest users, no stricter privacy settings are available.

When an account is opened on most services, the default settings automatically make it possible for postings to be public and for certain types of data to be displayed, such as location. The users themselves have to override this by setting their profile to “private” and deactivating the GPS function. If they fail to do so, the risk of undesirable advances is heightened. Abusers are usually experienced users, meaning that they gravitate toward portals that have low security settings, provide no option for reporting incidents, and allow for searches according to age. It is therefore recommended to block contact attempts from outsiders by turning off the comment function and designating all personal profiles as “private”. In addition, one should see to it that profiles cannot be located via search engine (as on Instagram, for example) and that GPS functions are deactivated (the Snap Map, for example, displays the user’s location live). Moreover, it is wise to restrict the exchange of messages to friends, meaning: to persons one also knows offline.

Blocking undesirable advances – the example of WhatsApp

What is WhatsApp?

WhatsApp is a messenger service which has been owned by Facebook Inc. since 2014. It enables users to post short messages, photos, videos, files, contacts, and the user’s location via a smartphone. For years now, WhatsApp has been one of the three most popular internet offerings among 12-to-19-year-olds in Germany (mpfs, 2018, p. 34). The service is used predominantly for individual communication, from smartphone to smartphone. However, it also enables the creation of a group, in which a number of participants can exchange simultaneously with one another. The terms and conditions state that the minimal age for users is 16, or 13 with parental permission, but there is no verification system in place that could check the users’ actual age (WhatsApp, 2020a). In today’s reality, even elementary school classes already have their own WhatsApp groups.

Establishing contact via messenger

The functionality of the messenger makes it possible for strangers to initiate contact with children or adolescents once their telephone number is known. Exchanging photos and videos, posting status videos, or chatting and phoning via messenger are then a simple matter. As soon as a person has been included in a group, they also have access to the telephone numbers of all other participants in the group, as well as other contact information that has been made public (profile photo, status, and so on).

Many adolescents assume, when using the popular messenger, that they are in a safe space; they are unaware of the exposed nature of this messenger service that makes it possible to be contacted by strangers. It is therefore essential that young people become familiar with and make use of the service’s options for blocking, reporting, and deleting (WhatsApp, 2020b). Parents or other guardians should see to it that the proper settings are installed when an account is first created.

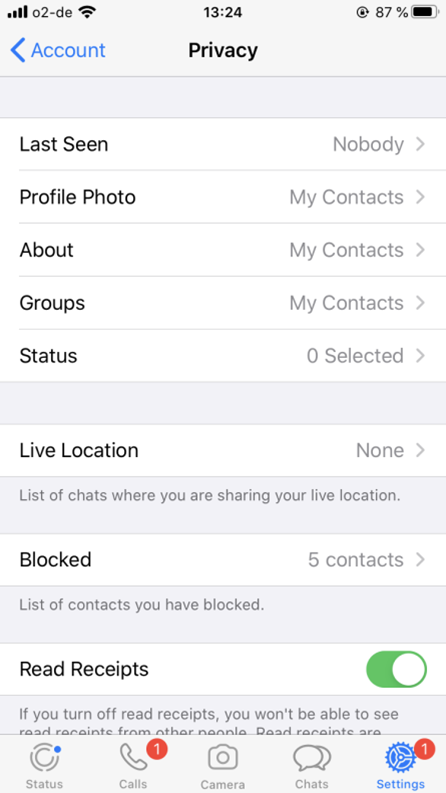

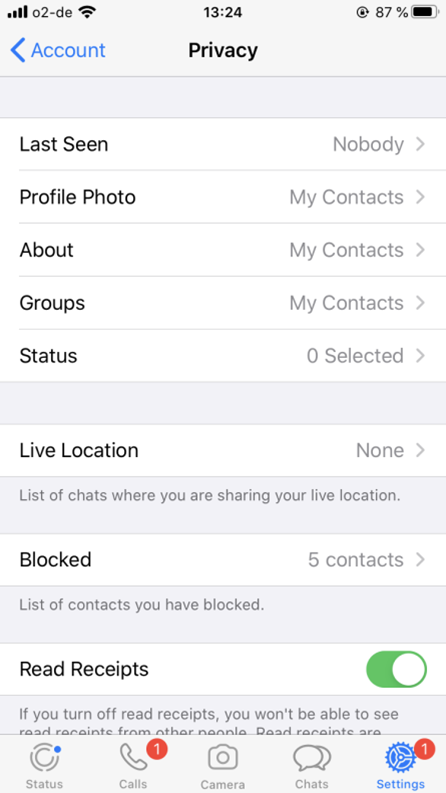

Illustration 1 – Secure pre-settings on an iPhone 7

Illustration 1 – Secure pre-settings on an iPhone 7© German Safer Internet Centre

(Live) location function should be disabled

On WhatsApp, users can post their current location as an element in a message, or can share their current location over a self-defined period of time, as a kind of “live broadcast”. This option should not be chosen within groups that include strangers, since sharing location data facilitates stalking – which is frequently an element of cybergrooming.

Protecting oneself with secure settings

To provide as little information about oneself as possible to strangers, one can adjust data protection settings so that access to the profile photo, personal information, status, and so on, is denied to anyone who is not listed as a contact in the personal phonebook. In this context, it is important that adolescents select their contacts judiciously, listing in their phonebook only people they actually know. This kind of contact “housekeeping” for one’s own protection requires a certain maturity and the ability to foresee consequences – things that children first need to be encouraged to learn.

Prevention begins at home

Although young people give the impression of effortlessly grasping the use of online services and mastering the technical handling of devices much more smoothly than their parents, they fall far behind in their ability to judge the consequences of engaging uncritically with the online world (klicksafe, 2018).

Parents, on the other hand, report in personal talks – at parents’ meetings or in individual counselling run by the help line Nummer gegen Kummer – that they do not feel confident when it comes to media education for their children, particularly in connection with online acquaintances. Providing information and counselling can, however, support parents in overcoming their hesitation, teach them to recognise warning signals, and to integrate protective steps into the everyday upbringing of their children.

More safety on social media – tips for parents

When children are getting to know and learning to use popular portals, it is important that they are not left to deal with all this by themselves. Parents should be talking to their kids about it, empowering and encouraging them to get help if something unpleasant or embarrassing happens. This implies discussing, early on, who can be trusted and who to turn to when help is needed. From the outset, young users should also know about support provided by counselling services.

In this context, prevention means escorting children and adolescents along their way, setting up a framework in which it is uncomplicated for them to talk openly about their experiences in the digital realm. It also means teaching children how to behave towards others on the internet. Part of their learning about netiquette consists of understanding that they themselves have every right to abruptly break off contact with someone who is not behaving acceptably, who is violating their privacy or their dignity. Their own feelings are reliable indicators, to be taken seriously; children are allowed to say “no” to a situation that makes them uncomfortable. Besides, they should refrain from making others feel uncomfortable: parents should begin exchanging with children at an early age about their right to privacy and about respecting the privacy of others. It is also wise to begin early on to explain to children why photos and videos need to be handled with care, and that the persons shown in the images must have control over who is allowed to see them.

This is a challenge for parents – to show genuine interest, to have matters explained to them, and to admit that they themselves are not perfect, but are trying to do their best. One common issue causing conflict in families is the age limit on popular online services. Parents need to be aware that social networks do not ensure sufficient security – for example, when they allow strangers to initiate contact. For this reason, parents should take the age limits that are set by the providers seriously. They should talk about it with their children, reach decisions, and establish rules (klicksafe, 2018).

In order to prevent cybergrooming, parents should examine the safety settings closely on every new service the children wish to install. Together with the children, they can discuss the information that is being requested and provided, then adjust the settings on the service to protect that information adequately. Personal data – including name, date of birth, address, and so on – should never be shared publicly or made available to strangers. Even when adolescents are already using social media services on their own, it is still advisable that parents continue to discuss privacy settings with them and repeatedly review the settings together, since it frequently occurs during an automatic update that the software reverts to its default settings.

It is sensible to cultivate, together, an awareness of the anonymity on the internet and the unfortunate openings this presents for people who wish to conceal their identity and their intentions.

A healthy mistrust towards the aims and pursuits of others is a useful tool that parents can teach children to keep at hand when they are online. Overall, it is wise to discuss together which individuals the children are allowed to cultivate contact with when they are online (klicksafe, 2018). In general, it is recommended to refuse contact requests from strangers, to discontinue contacts that are unpleasant while blocking or reporting the offending party, and to seek help whenever indicated.

Recognising cybergrooming tactics

Timely discussions at home with parents can help children and adolescents identify warning signals for cybergrooming more quickly, therefore putting up better defenses. One element of this is enabling young people to recognise the typical pitches used by potential abusers, who usually begin with harmless chatter.

How do people proceed when they have sexual fantasies or intentions towards minors? They try to gain young people’s trust by showering them with praise or compliments, and/or they bait them with unrealistic promises (often coupled with the expectation of becoming famous). They ask very personal questions (among other things, about sexual experience); they may ask the child or adolescent to post intimate photos. Sometimes, these images are later used for blackmail. Often, the strangers suggest switching over to private chats or messengers, the aim usually being to arrange a personal meeting (Pöting, 2019).

Because most potential abusers proceed strategically and deliberately target certain young individuals – chosen due to vulnerabilities or weaknesses observed online – it is essential that particularly endangered minors receive support from adults (UBSKM, 2020b). These may include children and adolescents who see themselves as outsiders, or those growing up in authoritarian family systems or families where violence dominates or sexuality is taboo (ibid.).

In order to identify cybergrooming advances early on or block them entirely, it is essential that the perpetrator does not succeed in winning the confidence of a young person to the point where they keep the contact secret from those in their social surrounding. In particular, young girls and adolescents prone to taking risks and receptive to issues of sexuality form an especially endangered target group. Offering information and counsel to parents, classmates, and siblings can contribute towards involving people of trust, while calling attention to supportive aspects that can improve the situation for all those involved – such as emotional stability and approaches to sexuality without taboos (Osterheider & Neutze, 2015, p. 4).

Conversations about sexual abuse

It is a prerequisite for protecting children and adolescents from cybergrooming that, in the home, sex education be integrated into an upbringing based on body integrity and sexual self-determination. Learning to acknowledge one’s own boundaries and the boundaries of others, and understanding what mutual consent means are of the essence. This can help children to identify sexualised advances on the internet more easily, to take their own feelings seriously, and to know how to resist such advances and where to seek help. It is seminal to this approach that prevention be treated as an everyday matter and that parents “be sensitive to the concerns of their children, never subjugating the children’s needs to their own” (UBSKM, 2020a). This includes talking to one another about one’s own feelings, about setting boundaries, or about how secrets are dealt with within the family.

Discussing the topic of self-portrayal on the internet is also a necessity. Parents are advised to negotiate norms for it with their children and also discuss the possible consequences of a portrayal that appears permissive or libertine. In fact, the parents themselves are often in need of education about the manner in which everyday photos (that they or their children post unthinkingly) can be sexualised on the internet: placed into a different context and transformed into a violation of the intimate privacy of the persons depicted (Giertz et al., 2019: 14). In this context, the authors at jugendschutz.net call attention to the re-use of everyday photos and videos – often those taken at the beach or during sports – by paedophiles who attach suggestive comments, create playlists, or disseminate the images in forums for like-minded viewers.

Another significant aspect is the issue of how parents or guardians treat the topic of guilt and shame. Perpetrators often rely on the loyalty of their victims, assuming that the latter will not tell anyone what has occurred – especially if the incident was precipitated by risky behaviour on the young person’s part (such as posting suggestive photos on social networks). Prevention should not be restricted to simply warning young people about such mistakes. It also needs to be made clear that even risky behaviour, however short-sighted, is no reason to develop guilt feelings (UBSKM, 2020a).

What is most important for children and adolescents is being given the message that they can speak with their parents about cybergrooming or sexual abuse, that they are not the ones at fault, that their parents will believe them and help them and/or organise professional support.

On the practical level, education about cybergrooming or sexual abuse should be tailored appropriately to the age of the child, should avoid frightening younger children, and should set in when they begin school, at the earliest. Growing up, they should be aware that:

- girls and boys can be exposed to sexual violence;

- that men, but also adolescents and sometimes women can be the perpetrators;

- that most adults and adolescents are not abusers;

- that most perpetrators keep their intentions secret;

- that abusers are often individuals one is familiar with, and seldom are strangers;

- that sexual abuse has nothing to do with love;

- that abuse often begins with odd feelings;

- that girls and boys can also encounter sexual violence in chat rooms;

- and that there can be sexual transgressions among children and adolescents, and that in such cases one has a right to receive help (UBSKM, 2020a).

Although prevention cannot provide absolute protection against abuse, it helps in identifying cases early and in terminating contact. Furthermore, well-informed children and adolescents are less susceptible, can size up situations more accurately, and are better able to talk about them (ibid.).

Parents can take precautions against cybergrooming through preventive efforts and can intervene more effectively when incidents do occur if they, on the one hand, show understanding for the needs of those who were targeted (by listening and providing support), and on the other hand have acquired the knowledge necessary for an appropriate response. This could include documentation of proof and filing of legal charges; blocking a user and making a report to the provider or a complaint to a hotline or support agency; arranging professional support or counselling (Pöting, 2019).

Prevention in schools and in youth recreation facilities

As experience in practical work with adolescents indicates, they clearly consider the topic of cybergrooming to be of interest and of relevance for their everyday lives. Due to the sexual and pornographic connotations, however, school students have certain inhibitions towards approaching this delicate topic with a closely knit social group – such as their class at school. What is more, individuals in the class may already have been victimised in some way, so that particular sensitivity is called for in broaching the topic. And if any incident should come to light, intervention methods involving external support and the parents will become necessary.

Initially, it is important to clarify in a matter-of-fact manner the concepts of cybergrooming, cybermobbing, and sexting, in order to create a common foundation of knowledge among the students. The typical approaches taken by abusers in cybergrooming need to be discussed in the classroom, along with the prosecutable offences that occur (sexual assault, blackmail, sexual abuse, violation of the right to control one’s own image in photos or videos). These issues can form the basis for additional, methodically and didactically structured learning units permitting various and creative approaches. To illustrate this, several examples taken from media education practice will be presented in the following, including a peer-mentoring approach, a meme-reaction app, work with a topically related film, and an action-oriented method.

Example 1: Peer-to-peer approach – developing a get savvy campaign for younger students

Campaigns that have been developed in various countries on the topic of cybergrooming can be presented at the outset of the learning unit Sexting – Risks and Side Effects; examples and materials are provided in the klicksafe teaching unit Selfies, Sexting, Self-Portrayal (Rack & Sauer, 2018, particularly pp. 40-48). The students are then allowed to plan an action of their own – either a short production (such as a cellphone video), a campaign (such as a poster), or information material (such as a flyer) on the subject of cybergrooming, intended for outreach to younger students as a target group. The whole class votes on which idea they will implement together in the next step. In general, it is quite productive to have older students informing younger ones in the sense of a peer-mentoring approach as applied, for example, by the Mediascouts (Medienscouts NRW, 2020).

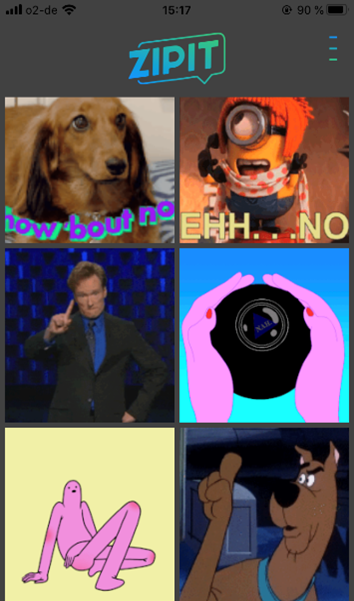

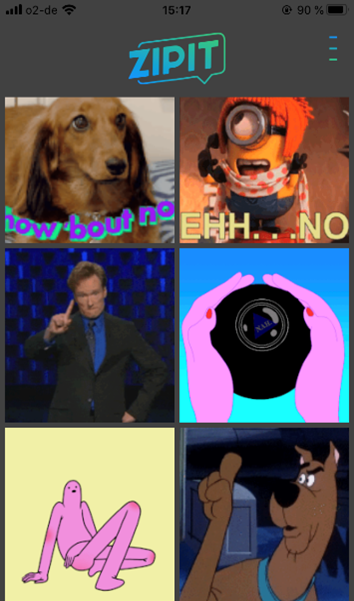

Illustration 2 – zipit app

© German Safer Internet Centre

Example 2: Humour puts an end to grooming – zipit

One aim of good preventative work should be to give young people practical options for taking action should they ever become the target of sexual advances. With the zipit app, developed by the media education project Childline in England, students receive suggestions for memes with which they can respond to explicit advances on social media – and respond authentically in a form familiar to them, with pictures (Childline, 2020). The images can be downloaded from the app’s gallery directly into the photo storage on one’s own phone. In the event that an undesirable grooming situation comes up, one can send off the meme as a way of terminating the contact early and with self-assurance.

Example 3: Pedagogical work with a film – The White Rabbit

The film The White Rabbit (“Das weiße Kaninchen”), produced by the Südwestrundfunk, graphically illustrates the various forms of cybergrooming, from first advances to ultimate dependency from which the victim can no longer escape without outside help. A corresponding classroom unit made available by the Media Competency Forum Southwest enables the analysis of key scenes by suggesting approaches for discussion, such as a focus on the responsibility of others with the question “When and how could others have intervened?” (MKFS, 2020). An exercise on the theme “Everyone has boundaries – how far would you go?” demonstrates to the group that individuals set their boundaries differently, but that all boundaries are to be accepted. Other exercises relating to trust and abuse of trust are also included as part of a comprehensive conception for prevention.

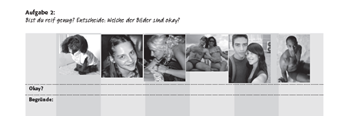

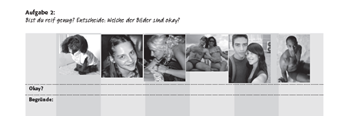

Illustration 3 – “Are you mature enough? Which pictures are OK?” Screenshot material from Let’s talk about porn, p. 68

Example 4: Preventive work with the klicksafe materials Let’s talk about porn and selfies, sexting, self-portrayal

Let’s talk about porn, intended for use in schools and youth work, addresses not only the use of pornography, but also the issue of overstepping intimate boundaries, and problems associated with sexualised self-portrayals. Here, young people learn to reflect critically about online postings of suggestive self-images (Kimmel, Rack, Schnell, Hahn, & Hartl, 2018, pp. 66-68) and to realistically estimate the risks related to libertine images on the internet. The adolescents make decisions on posting images privately or publicly, give reasons for their decisions, and learn how to proceed when their own private information is published by third parties. One of the many work projects included, the project Sexy Chat, aims at learning how to recognise alarm signals in chat situations that seem suspect, and how to react when explicit advances are made. The aspect of anonymity is taken up in a spot on the topic of Cybersex, weighing the issues of anonymity and identity on the internet – and the associations triggered by nicknames, as in Illustration 4 (cf. short video at Veiliginternetten, 2001).

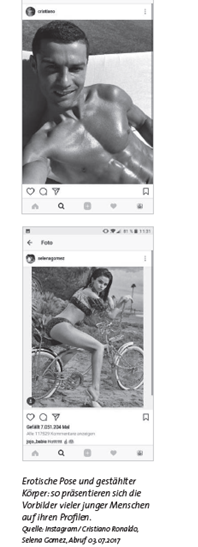

Illustration 4 – What is behind the nickname: “HardCore Barbie”? Why this person? Are you sure? Screenshot from Let’s talk about porn, p. 121

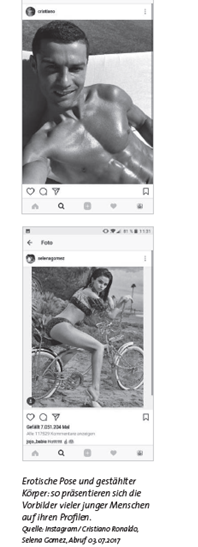

Illustration 4 – What is behind the nickname: “HardCore Barbie”? Why this person? Are you sure? Screenshot from Let’s talk about porn, p. 121 Illustration 5 – Steeled body, erotic pose – how the role models of many young people present themselves in profiles. Instagram images Cristiano Ronaldo and Selena Gomez, retrieved on July 3, 2017. Screenshot from Selfie, Sexting, Self-Portrayal, p. 24

Illustration 5 – Steeled body, erotic pose – how the role models of many young people present themselves in profiles. Instagram images Cristiano Ronaldo and Selena Gomez, retrieved on July 3, 2017. Screenshot from Selfie, Sexting, Self-Portrayal, p. 24Another instruction package called Selfies, Sexting, Self-Portrayal includes a section on teenagers’ idols, casting them as rather questionable role models that can induce children and adolescents to post sexualised images of themselves (Rack & Sauer, 2018, pp. 24-25). In a reflexive process, they consider the extent to which they allow themselves to be influenced by such misleading role models in their own representation of themselves.

Perspectives

To a great extent, the internet is an anonymous space that enables individuals to assume false identities. Particularly in chats, messengers, and other digital locations that facilitate communication in separate areas (such as private chats), this anonymity presents considerable dangers. Preventive efforts undertaken by parents, schools, and youth workers attempt to prepare young people for the cybergrooming pitfalls they are likely to encounter, and to provide them with tools for self-protection that can be used in an emergency. In order to prevent online victimisation, much needs to be done: gender- and age-specific measures, programmes addressing self-assertion and the right to draw boundaries in the virtual world. Addressing these topics in the classroom can help older children and adolescents to become knowledgeable about potential consequences, and to learn about being proactive in matters of prevention and intervention.

For younger children of pre-school and elementary school age, other measures are indicated: digitally protected areas screened off by technical shields play a significant role, along with parental supervision and concern. An equally important preventive measure is adequate sex education in accordance with the children’s age and development, as well as matter-of-fact information on the topic of sexual abuse.

The German awareness centre klicksafe sees it as part of its mandate to inform various target groups about the safety risks involved in digital communication. This encompasses calling attention to the typical strategies employed in cybergrooming and sexual harassment and providing support for preventive self-help through offerings designed to empower parents, children, and adolescents to defend themselves against undesirable contact pitches coming in over the net. On its website, under https://www.klicksafe.de/materialien, klicksafe presents a wide variety of information materials and teaching units on these topics, which alongside the prevention of cybergrooming also include related areas, such as secure use of social media, protection of the private sphere, and issues surrounding sexualised self-portrayal and sexting/sextortion.

klicksafe is an initiative of the European Union, coordinated and implemented by the LMK – Media Authority of Rhineland-Palatinate (coordinator) and die State Media Authority of North Rhine-Westphalia. Since 2004, klicksafe, as the national awareness centre for Germany, has been pursuing its goal of promoting media literacy and supporting users in handling the internet and digital media competently and critically. In doing so, klicksafe realises the European “Better Internet for Kids” strategy in Germany. klicksafe provides comprehensive information on current issues relating to digital media and their responsible use. The initiative also explicitly addresses multipliers, educators including teachers and youth workers, parents and guardians. Together with its national and European partners, the klicksafe team develops pedagogical conceptions and materials for parents, schools, and those working with children and adolescents in non-academic environments.

References and sources

All over the world, child welfare organisations are working to protect girls and boys from sexualised violence in real life, and also on the internet. However, the sexual exploitation of girls and boys rests on traditions stretching over centuries, and it was not until the 1990s that pedagogical prevention efforts were undertaken and began raising awareness in kindergartens, schools, counselling services and youth authorities towards providing timely support to children and adolescents (Enders, 1990, p. 11).

Nowadays, it is no longer an exception to encounter depictions of abuse, harassment, and cybergrooming on the internetnet. The anonymity in the online world enables adults in disguise to establish contacts with children, to elicit information about sexual matters, and in the worst case, to pave the way for abuse in real life.

The study Online Experience of 9-to-17-Year-Olds conducted by EU Kids Online in 2019 (Hasebrink, Lampert, & Thiel, 2019) revealed that in Germany, 34 per cent of the girls surveyed and 23 per cent of the boys surveyed had been confronted online with intimate or suggestive questions that they did not want to answer. The topical spectrum ranges from questions about sexual experience and preferences to explicit prompting of sexual acts. Older kids seem to be targeted much more frequently, with an occurrence of 15 per cent among 12-to-14-year-olds rising to 43 per cent in the 15-to-17 age group.

With regards to the frequency of grooming, it seems to occur here and there: about one quarter of those surveyed reported occasional attempts they had been confronted with. Among them, one in five said that, during the past year, they had experienced it at least once a month (ibid., p. 25).

The sexual harassment of children and adolescents takes place predominantly on platforms that also address adults and that, in addition to their public areas, offer private communication functions as found in social media and online games. Many of these services are inadequately moderated, and their pre-installed settings do not provide sufficient protection for users. As a result, the risks are especially high (jugendschutz.net, 2019, p. 12).

Statistics from the 30 helplines cooperating in the European network Insafe show a slight increase in inquiries related to the topic of cybergrooming for the years 2018 und 2019 (data provided by the telephone helpline Nummer gegen Kummer). It can be assumed that girls and boys have increasing difficulty in dealing with advances made to them via cybergrooming, and that they therefore seek support.

About 6 per cent of 6-to-7-year-olds in Germany already have their own smartphone. In the 8-to-9-year-old age group, this rises to 33 per cent, and for the 10-to-11 year-olds, it reaches 75 per cent. Among the 12-to-13-year-olds, the proportion of smartphone owners already lies at 95 per cent (Tenzer, 2020, in a study for Bitkom Research Germany). Intelligent mobile phones have become, for many, an essential part of everyday life. Using them brings the popular social media services and communication platforms directly into the lives of children and adolescents.

Practical media education work by the authors with parents, children, and adolescents has shown that very few children and adolescents possess the knowledge necessary for dealing with harassment and sexualised advances. Moreover, younger children in particular are moving about on social media without sufficient technical protection. Many of the popular services are oriented towards interaction and offer options to establish contact – including contact to users who are minors.

All this makes it imperative for children and adolescents to be prepared early for the risks that their use of communication services and social media is very likely to entail. They need to be taught how they can protect themselves from risky contacts and how to react when unpleasant encounters do occur. Prevention implies assuming a position oriented to resources, and emphasising behaviour aimed at resolving conflicts and strategies to protect oneself and others. The focus lies on information, empowerment, and support for children and adolescents. They need information on the risks of the internet and the questionability of posting personal information and images. Once something is on the internet, it becomes very difficult to delete.

The significance of social media for cybergrooming

Young people use the internet preferentially for communication, exchanging or sharing news, photos, or videos with others (mpfs, 2018, p. 34). This makes messenger services and social networks such as WhatsApp, Instagram und Snapchat particularly popular among young users (ibid., p. 39). The app TikTok, which has become known as a playback app, has also gained a following in Germany in recent years particularly among younger girls, and has generated a rash of negative headlines due to cybergrooming cases (Pöting, 2018; jugendschutz.net, 2020). Although social media are used by adolescents primarily for contacts within their own circles, there is nonetheless the possibility that outsiders will use these services to establish contact, or that the young people themselves will cultivate contacts to persons they only know on the net. Outsiders can make contact particularly easily through social media and online games – such as Minecraft or Clash of Clans – that present interactive options: comments, chats, or the like.

Consequently, potential abusers create accounts on social media for the purpose of initiating sexualized relationships (Tagesspiegel, 2019; Giertz, Hautz, Link, & Wahl, 2019, p. 12-13). One typical tactic taken by cybergroomers – persons deliberately contacting minors via social media in order to make sexual advances – is to initiate contact by commenting on content that has been posted on a publicly accessible profile. This means that they begin an exchange in an open chat with the aim of proceeding to a private conversation, for example by shifting to the “direct” function on Instagram.

Platform providers do in fact set an age minimum for users, but they do not enforce it. As a result, there are elementary school children using apps whose terms and conditions stipulate 13 as a minimum age. It follows that, for these youngest users, no stricter privacy settings are available.

When an account is opened on most services, the default settings automatically make it possible for postings to be public and for certain types of data to be displayed, such as location. The users themselves have to override this by setting their profile to “private” and deactivating the GPS function. If they fail to do so, the risk of undesirable advances is heightened. Abusers are usually experienced users, meaning that they gravitate toward portals that have low security settings, provide no option for reporting incidents, and allow for searches according to age. It is therefore recommended to block contact attempts from outsiders by turning off the comment function and designating all personal profiles as “private”. In addition, one should see to it that profiles cannot be located via search engine (as on Instagram, for example) and that GPS functions are deactivated (the Snap Map, for example, displays the user’s location live). Moreover, it is wise to restrict the exchange of messages to friends, meaning: to persons one also knows offline.

Blocking undesirable advances – the example of WhatsApp

What is WhatsApp?

WhatsApp is a messenger service which has been owned by Facebook Inc. since 2014. It enables users to post short messages, photos, videos, files, contacts, and the user’s location via a smartphone. For years now, WhatsApp has been one of the three most popular internet offerings among 12-to-19-year-olds in Germany (mpfs, 2018, p. 34). The service is used predominantly for individual communication, from smartphone to smartphone. However, it also enables the creation of a group, in which a number of participants can exchange simultaneously with one another. The terms and conditions state that the minimal age for users is 16, or 13 with parental permission, but there is no verification system in place that could check the users’ actual age (WhatsApp, 2020a). In today’s reality, even elementary school classes already have their own WhatsApp groups.

Establishing contact via messenger

The functionality of the messenger makes it possible for strangers to initiate contact with children or adolescents once their telephone number is known. Exchanging photos and videos, posting status videos, or chatting and phoning via messenger are then a simple matter. As soon as a person has been included in a group, they also have access to the telephone numbers of all other participants in the group, as well as other contact information that has been made public (profile photo, status, and so on).

Many adolescents assume, when using the popular messenger, that they are in a safe space; they are unaware of the exposed nature of this messenger service that makes it possible to be contacted by strangers. It is therefore essential that young people become familiar with and make use of the service’s options for blocking, reporting, and deleting (WhatsApp, 2020b). Parents or other guardians should see to it that the proper settings are installed when an account is first created.

Illustration 1 – Secure pre-settings on an iPhone 7

Illustration 1 – Secure pre-settings on an iPhone 7© German Safer Internet Centre

(Live) location function should be disabled

On WhatsApp, users can post their current location as an element in a message, or can share their current location over a self-defined period of time, as a kind of “live broadcast”. This option should not be chosen within groups that include strangers, since sharing location data facilitates stalking – which is frequently an element of cybergrooming.

Protecting oneself with secure settings

To provide as little information about oneself as possible to strangers, one can adjust data protection settings so that access to the profile photo, personal information, status, and so on, is denied to anyone who is not listed as a contact in the personal phonebook. In this context, it is important that adolescents select their contacts judiciously, listing in their phonebook only people they actually know. This kind of contact “housekeeping” for one’s own protection requires a certain maturity and the ability to foresee consequences – things that children first need to be encouraged to learn.

Prevention begins at home

Although young people give the impression of effortlessly grasping the use of online services and mastering the technical handling of devices much more smoothly than their parents, they fall far behind in their ability to judge the consequences of engaging uncritically with the online world (klicksafe, 2018).

Parents, on the other hand, report in personal talks – at parents’ meetings or in individual counselling run by the help line Nummer gegen Kummer – that they do not feel confident when it comes to media education for their children, particularly in connection with online acquaintances. Providing information and counselling can, however, support parents in overcoming their hesitation, teach them to recognise warning signals, and to integrate protective steps into the everyday upbringing of their children.

More safety on social media – tips for parents

When children are getting to know and learning to use popular portals, it is important that they are not left to deal with all this by themselves. Parents should be talking to their kids about it, empowering and encouraging them to get help if something unpleasant or embarrassing happens. This implies discussing, early on, who can be trusted and who to turn to when help is needed. From the outset, young users should also know about support provided by counselling services.

In this context, prevention means escorting children and adolescents along their way, setting up a framework in which it is uncomplicated for them to talk openly about their experiences in the digital realm. It also means teaching children how to behave towards others on the internet. Part of their learning about netiquette consists of understanding that they themselves have every right to abruptly break off contact with someone who is not behaving acceptably, who is violating their privacy or their dignity. Their own feelings are reliable indicators, to be taken seriously; children are allowed to say “no” to a situation that makes them uncomfortable. Besides, they should refrain from making others feel uncomfortable: parents should begin exchanging with children at an early age about their right to privacy and about respecting the privacy of others. It is also wise to begin early on to explain to children why photos and videos need to be handled with care, and that the persons shown in the images must have control over who is allowed to see them.

This is a challenge for parents – to show genuine interest, to have matters explained to them, and to admit that they themselves are not perfect, but are trying to do their best. One common issue causing conflict in families is the age limit on popular online services. Parents need to be aware that social networks do not ensure sufficient security – for example, when they allow strangers to initiate contact. For this reason, parents should take the age limits that are set by the providers seriously. They should talk about it with their children, reach decisions, and establish rules (klicksafe, 2018).

In order to prevent cybergrooming, parents should examine the safety settings closely on every new service the children wish to install. Together with the children, they can discuss the information that is being requested and provided, then adjust the settings on the service to protect that information adequately. Personal data – including name, date of birth, address, and so on – should never be shared publicly or made available to strangers. Even when adolescents are already using social media services on their own, it is still advisable that parents continue to discuss privacy settings with them and repeatedly review the settings together, since it frequently occurs during an automatic update that the software reverts to its default settings.

It is sensible to cultivate, together, an awareness of the anonymity on the internet and the unfortunate openings this presents for people who wish to conceal their identity and their intentions.

A healthy mistrust towards the aims and pursuits of others is a useful tool that parents can teach children to keep at hand when they are online. Overall, it is wise to discuss together which individuals the children are allowed to cultivate contact with when they are online (klicksafe, 2018). In general, it is recommended to refuse contact requests from strangers, to discontinue contacts that are unpleasant while blocking or reporting the offending party, and to seek help whenever indicated.

Recognising cybergrooming tactics

Timely discussions at home with parents can help children and adolescents identify warning signals for cybergrooming more quickly, therefore putting up better defenses. One element of this is enabling young people to recognise the typical pitches used by potential abusers, who usually begin with harmless chatter.

How do people proceed when they have sexual fantasies or intentions towards minors? They try to gain young people’s trust by showering them with praise or compliments, and/or they bait them with unrealistic promises (often coupled with the expectation of becoming famous). They ask very personal questions (among other things, about sexual experience); they may ask the child or adolescent to post intimate photos. Sometimes, these images are later used for blackmail. Often, the strangers suggest switching over to private chats or messengers, the aim usually being to arrange a personal meeting (Pöting, 2019).

Because most potential abusers proceed strategically and deliberately target certain young individuals – chosen due to vulnerabilities or weaknesses observed online – it is essential that particularly endangered minors receive support from adults (UBSKM, 2020b). These may include children and adolescents who see themselves as outsiders, or those growing up in authoritarian family systems or families where violence dominates or sexuality is taboo (ibid.).

In order to identify cybergrooming advances early on or block them entirely, it is essential that the perpetrator does not succeed in winning the confidence of a young person to the point where they keep the contact secret from those in their social surrounding. In particular, young girls and adolescents prone to taking risks and receptive to issues of sexuality form an especially endangered target group. Offering information and counsel to parents, classmates, and siblings can contribute towards involving people of trust, while calling attention to supportive aspects that can improve the situation for all those involved – such as emotional stability and approaches to sexuality without taboos (Osterheider & Neutze, 2015, p. 4).

Conversations about sexual abuse

It is a prerequisite for protecting children and adolescents from cybergrooming that, in the home, sex education be integrated into an upbringing based on body integrity and sexual self-determination. Learning to acknowledge one’s own boundaries and the boundaries of others, and understanding what mutual consent means are of the essence. This can help children to identify sexualised advances on the internet more easily, to take their own feelings seriously, and to know how to resist such advances and where to seek help. It is seminal to this approach that prevention be treated as an everyday matter and that parents “be sensitive to the concerns of their children, never subjugating the children’s needs to their own” (UBSKM, 2020a). This includes talking to one another about one’s own feelings, about setting boundaries, or about how secrets are dealt with within the family.

Discussing the topic of self-portrayal on the internet is also a necessity. Parents are advised to negotiate norms for it with their children and also discuss the possible consequences of a portrayal that appears permissive or libertine. In fact, the parents themselves are often in need of education about the manner in which everyday photos (that they or their children post unthinkingly) can be sexualised on the internet: placed into a different context and transformed into a violation of the intimate privacy of the persons depicted (Giertz et al., 2019: 14). In this context, the authors at jugendschutz.net call attention to the re-use of everyday photos and videos – often those taken at the beach or during sports – by paedophiles who attach suggestive comments, create playlists, or disseminate the images in forums for like-minded viewers.

Another significant aspect is the issue of how parents or guardians treat the topic of guilt and shame. Perpetrators often rely on the loyalty of their victims, assuming that the latter will not tell anyone what has occurred – especially if the incident was precipitated by risky behaviour on the young person’s part (such as posting suggestive photos on social networks). Prevention should not be restricted to simply warning young people about such mistakes. It also needs to be made clear that even risky behaviour, however short-sighted, is no reason to develop guilt feelings (UBSKM, 2020a).

What is most important for children and adolescents is being given the message that they can speak with their parents about cybergrooming or sexual abuse, that they are not the ones at fault, that their parents will believe them and help them and/or organise professional support.

On the practical level, education about cybergrooming or sexual abuse should be tailored appropriately to the age of the child, should avoid frightening younger children, and should set in when they begin school, at the earliest. Growing up, they should be aware that:

- girls and boys can be exposed to sexual violence;

- that men, but also adolescents and sometimes women can be the perpetrators;

- that most adults and adolescents are not abusers;

- that most perpetrators keep their intentions secret;

- that abusers are often individuals one is familiar with, and seldom are strangers;

- that sexual abuse has nothing to do with love;

- that abuse often begins with odd feelings;

- that girls and boys can also encounter sexual violence in chat rooms;

- and that there can be sexual transgressions among children and adolescents, and that in such cases one has a right to receive help (UBSKM, 2020a).

Although prevention cannot provide absolute protection against abuse, it helps in identifying cases early and in terminating contact. Furthermore, well-informed children and adolescents are less susceptible, can size up situations more accurately, and are better able to talk about them (ibid.).

Parents can take precautions against cybergrooming through preventive efforts and can intervene more effectively when incidents do occur if they, on the one hand, show understanding for the needs of those who were targeted (by listening and providing support), and on the other hand have acquired the knowledge necessary for an appropriate response. This could include documentation of proof and filing of legal charges; blocking a user and making a report to the provider or a complaint to a hotline or support agency; arranging professional support or counselling (Pöting, 2019).

Prevention in schools and in youth recreation facilities

As experience in practical work with adolescents indicates, they clearly consider the topic of cybergrooming to be of interest and of relevance for their everyday lives. Due to the sexual and pornographic connotations, however, school students have certain inhibitions towards approaching this delicate topic with a closely knit social group – such as their class at school. What is more, individuals in the class may already have been victimised in some way, so that particular sensitivity is called for in broaching the topic. And if any incident should come to light, intervention methods involving external support and the parents will become necessary.

Initially, it is important to clarify in a matter-of-fact manner the concepts of cybergrooming, cybermobbing, and sexting, in order to create a common foundation of knowledge among the students. The typical approaches taken by abusers in cybergrooming need to be discussed in the classroom, along with the prosecutable offences that occur (sexual assault, blackmail, sexual abuse, violation of the right to control one’s own image in photos or videos). These issues can form the basis for additional, methodically and didactically structured learning units permitting various and creative approaches. To illustrate this, several examples taken from media education practice will be presented in the following, including a peer-mentoring approach, a meme-reaction app, work with a topically related film, and an action-oriented method.

Example 1: Peer-to-peer approach – developing a get savvy campaign for younger students

Campaigns that have been developed in various countries on the topic of cybergrooming can be presented at the outset of the learning unit Sexting – Risks and Side Effects; examples and materials are provided in the klicksafe teaching unit Selfies, Sexting, Self-Portrayal (Rack & Sauer, 2018, particularly pp. 40-48). The students are then allowed to plan an action of their own – either a short production (such as a cellphone video), a campaign (such as a poster), or information material (such as a flyer) on the subject of cybergrooming, intended for outreach to younger students as a target group. The whole class votes on which idea they will implement together in the next step. In general, it is quite productive to have older students informing younger ones in the sense of a peer-mentoring approach as applied, for example, by the Mediascouts (Medienscouts NRW, 2020).

Illustration 2 – zipit app

© German Safer Internet Centre

Example 2: Humour puts an end to grooming – zipit

One aim of good preventative work should be to give young people practical options for taking action should they ever become the target of sexual advances. With the zipit app, developed by the media education project Childline in England, students receive suggestions for memes with which they can respond to explicit advances on social media – and respond authentically in a form familiar to them, with pictures (Childline, 2020). The images can be downloaded from the app’s gallery directly into the photo storage on one’s own phone. In the event that an undesirable grooming situation comes up, one can send off the meme as a way of terminating the contact early and with self-assurance.

Example 3: Pedagogical work with a film – The White Rabbit

The film The White Rabbit (“Das weiße Kaninchen”), produced by the Südwestrundfunk, graphically illustrates the various forms of cybergrooming, from first advances to ultimate dependency from which the victim can no longer escape without outside help. A corresponding classroom unit made available by the Media Competency Forum Southwest enables the analysis of key scenes by suggesting approaches for discussion, such as a focus on the responsibility of others with the question “When and how could others have intervened?” (MKFS, 2020). An exercise on the theme “Everyone has boundaries – how far would you go?” demonstrates to the group that individuals set their boundaries differently, but that all boundaries are to be accepted. Other exercises relating to trust and abuse of trust are also included as part of a comprehensive conception for prevention.

Illustration 3 – “Are you mature enough? Which pictures are OK?” Screenshot material from Let’s talk about porn, p. 68

Example 4: Preventive work with the klicksafe materials Let’s talk about porn and selfies, sexting, self-portrayal

Let’s talk about porn, intended for use in schools and youth work, addresses not only the use of pornography, but also the issue of overstepping intimate boundaries, and problems associated with sexualised self-portrayals. Here, young people learn to reflect critically about online postings of suggestive self-images (Kimmel, Rack, Schnell, Hahn, & Hartl, 2018, pp. 66-68) and to realistically estimate the risks related to libertine images on the internet. The adolescents make decisions on posting images privately or publicly, give reasons for their decisions, and learn how to proceed when their own private information is published by third parties. One of the many work projects included, the project Sexy Chat, aims at learning how to recognise alarm signals in chat situations that seem suspect, and how to react when explicit advances are made. The aspect of anonymity is taken up in a spot on the topic of Cybersex, weighing the issues of anonymity and identity on the internet – and the associations triggered by nicknames, as in Illustration 4 (cf. short video at Veiliginternetten, 2001).

Illustration 4 – What is behind the nickname: “HardCore Barbie”? Why this person? Are you sure? Screenshot from Let’s talk about porn, p. 121

Illustration 4 – What is behind the nickname: “HardCore Barbie”? Why this person? Are you sure? Screenshot from Let’s talk about porn, p. 121 Illustration 5 – Steeled body, erotic pose – how the role models of many young people present themselves in profiles. Instagram images Cristiano Ronaldo and Selena Gomez, retrieved on July 3, 2017. Screenshot from Selfie, Sexting, Self-Portrayal, p. 24

Illustration 5 – Steeled body, erotic pose – how the role models of many young people present themselves in profiles. Instagram images Cristiano Ronaldo and Selena Gomez, retrieved on July 3, 2017. Screenshot from Selfie, Sexting, Self-Portrayal, p. 24Another instruction package called Selfies, Sexting, Self-Portrayal includes a section on teenagers’ idols, casting them as rather questionable role models that can induce children and adolescents to post sexualised images of themselves (Rack & Sauer, 2018, pp. 24-25). In a reflexive process, they consider the extent to which they allow themselves to be influenced by such misleading role models in their own representation of themselves.

Perspectives

To a great extent, the internet is an anonymous space that enables individuals to assume false identities. Particularly in chats, messengers, and other digital locations that facilitate communication in separate areas (such as private chats), this anonymity presents considerable dangers. Preventive efforts undertaken by parents, schools, and youth workers attempt to prepare young people for the cybergrooming pitfalls they are likely to encounter, and to provide them with tools for self-protection that can be used in an emergency. In order to prevent online victimisation, much needs to be done: gender- and age-specific measures, programmes addressing self-assertion and the right to draw boundaries in the virtual world. Addressing these topics in the classroom can help older children and adolescents to become knowledgeable about potential consequences, and to learn about being proactive in matters of prevention and intervention.

For younger children of pre-school and elementary school age, other measures are indicated: digitally protected areas screened off by technical shields play a significant role, along with parental supervision and concern. An equally important preventive measure is adequate sex education in accordance with the children’s age and development, as well as matter-of-fact information on the topic of sexual abuse.

The German awareness centre klicksafe sees it as part of its mandate to inform various target groups about the safety risks involved in digital communication. This encompasses calling attention to the typical strategies employed in cybergrooming and sexual harassment and providing support for preventive self-help through offerings designed to empower parents, children, and adolescents to defend themselves against undesirable contact pitches coming in over the net. On its website, under https://www.klicksafe.de/materialien, klicksafe presents a wide variety of information materials and teaching units on these topics, which alongside the prevention of cybergrooming also include related areas, such as secure use of social media, protection of the private sphere, and issues surrounding sexualised self-portrayal and sexting/sextortion.

klicksafe is an initiative of the European Union, coordinated and implemented by the LMK – Media Authority of Rhineland-Palatinate (coordinator) and die State Media Authority of North Rhine-Westphalia. Since 2004, klicksafe, as the national awareness centre for Germany, has been pursuing its goal of promoting media literacy and supporting users in handling the internet and digital media competently and critically. In doing so, klicksafe realises the European “Better Internet for Kids” strategy in Germany. klicksafe provides comprehensive information on current issues relating to digital media and their responsible use. The initiative also explicitly addresses multipliers, educators including teachers and youth workers, parents and guardians. Together with its national and European partners, the klicksafe team develops pedagogical conceptions and materials for parents, schools, and those working with children and adolescents in non-academic environments.

References and sources

- sexual exploitation Safer Internet Centre (SIC) grooming

Related content

- < Previous article

- Next article >