There are many discussions about the importance of media education for children and young people. In general - and understandably - the role of schools in teaching media competences is highlighted first and foremost. From this perspective, it is a bit surprising how little comprehensive information is available on how media education is implemented in practice. Saara Salomaa, Senior Adviser at the National Audiovisual Institute (KAVI), provides an overview of its implementation in the Finnish education system.

One opportunity for teaching media competences is given by Opeka. Opeka is an online tool for teachers and schools to measure and analyse their use of information and communication technology (ICT) in teaching. Tampere Research Center for Information and Media (TRIM) is responsible for the development of the service. Over the years, Opeka and related data collection tools have been funded by, for example, the Finnish National Agency for Education and the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Opeka's public performance reports span several years and are available to consult. For example, in 2020, there were a total of 3,594 respondents working in 20 different municipalities. The largest groups of respondents were teachers of different subjects, especially to young people (n = 1,410), and classroom teachers working with children aged 7–12 (n = 1,383). There were a total of 540 special education teachers among the respondents. There were also a small number of vocational schoolteachers (n = 76) and study counsellors (n = 70).

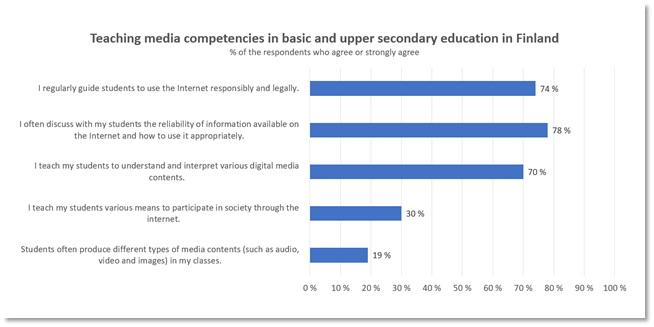

Like many other data collectors related to media education, Opeka was originally developed for the purpose of evaluation, rather than simply examining media education. Therefore, it is a matter of personal opinion to decide which of the evaluation tool's various statements to consider as indicators of media education. For this review, Saara Salomaa has selected five statements that describe moderately well the areas that are often considered important in media education:

- I regularly guide students to use the internet responsibly and legally.

- I often discuss with my students about the reliability of information available on the internet and how to use it appropriately.

- I teach my students to understand and interpret various digital media content.

- I teach my students various means to participate in society through the internet.

- Students often produce different types of media content (such as audio, video and images) in my classes.

Source: Opeka Yearly Report 2020

Based on the responses, it appears that the majority of teachers teach their students issues related to media interpretation, information reliability, and appropriate online behaviour. In contrast, teaching about participating in society is much less present.

However, it is particularly remarkable that only a minority of teachers offer classes that include students producing media content themselves. Fewer than one in five respondents somewhat agreed with the statement, even though the media content included here was as simple as pictures. Clearly, there is still work to be done to support students' own media production, which should be encouraged, for example, through further training and other development projects.

It is also interesting to observe that the technical readiness of a school, the attitudes of a teacher, or even the ICT skills of a teacher as such do not necessarily translate directly into teaching digital literacy practices. On a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being the worst and 4 being the best, technical capacity was assessed with an average of 3, attitudes with an average of 2.4, and ICT skills with an average of 2.1. Pedagogical use was clearly rated the weakest, receiving only an average of 1.7. The result provides an indication of how important it is, with regard to teachers’ training, to pay attention to the fact that teachers themselves should not solely be taught the general use of ICT. Long-term attention must be paid to the introduction and establishment of well-functioning and diverse pedagogical practices in everyday life inside classrooms.

Comparing the answers of different teacher groups, it can be stated that with these indicators, media education is more often implemented by those teachers who work with children in grades 3–6 (children aged 9–12). You can read more about Opeka's reports, such as the differences between different teacher groups and response years, in the Opeka Yearly Report 2020.

Find out more about the work of the Finnish Safer Internet Centre, including its awareness raising, helpline, hotline and youth participation services – or find similar information for Safer Internet Centres throughout Europe.

There are many discussions about the importance of media education for children and young people. In general - and understandably - the role of schools in teaching media competences is highlighted first and foremost. From this perspective, it is a bit surprising how little comprehensive information is available on how media education is implemented in practice. Saara Salomaa, Senior Adviser at the National Audiovisual Institute (KAVI), provides an overview of its implementation in the Finnish education system.

One opportunity for teaching media competences is given by Opeka. Opeka is an online tool for teachers and schools to measure and analyse their use of information and communication technology (ICT) in teaching. Tampere Research Center for Information and Media (TRIM) is responsible for the development of the service. Over the years, Opeka and related data collection tools have been funded by, for example, the Finnish National Agency for Education and the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Opeka's public performance reports span several years and are available to consult. For example, in 2020, there were a total of 3,594 respondents working in 20 different municipalities. The largest groups of respondents were teachers of different subjects, especially to young people (n = 1,410), and classroom teachers working with children aged 7–12 (n = 1,383). There were a total of 540 special education teachers among the respondents. There were also a small number of vocational schoolteachers (n = 76) and study counsellors (n = 70).

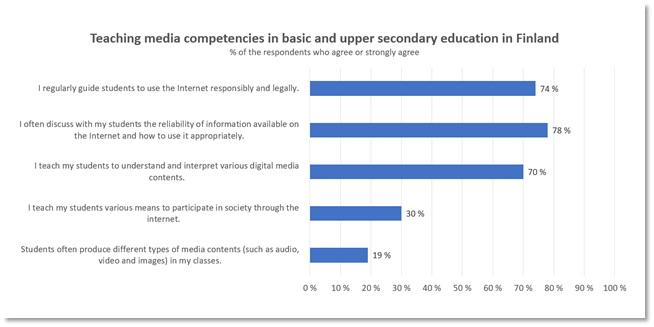

Like many other data collectors related to media education, Opeka was originally developed for the purpose of evaluation, rather than simply examining media education. Therefore, it is a matter of personal opinion to decide which of the evaluation tool's various statements to consider as indicators of media education. For this review, Saara Salomaa has selected five statements that describe moderately well the areas that are often considered important in media education:

- I regularly guide students to use the internet responsibly and legally.

- I often discuss with my students about the reliability of information available on the internet and how to use it appropriately.

- I teach my students to understand and interpret various digital media content.

- I teach my students various means to participate in society through the internet.

- Students often produce different types of media content (such as audio, video and images) in my classes.

Source: Opeka Yearly Report 2020

Based on the responses, it appears that the majority of teachers teach their students issues related to media interpretation, information reliability, and appropriate online behaviour. In contrast, teaching about participating in society is much less present.

However, it is particularly remarkable that only a minority of teachers offer classes that include students producing media content themselves. Fewer than one in five respondents somewhat agreed with the statement, even though the media content included here was as simple as pictures. Clearly, there is still work to be done to support students' own media production, which should be encouraged, for example, through further training and other development projects.

It is also interesting to observe that the technical readiness of a school, the attitudes of a teacher, or even the ICT skills of a teacher as such do not necessarily translate directly into teaching digital literacy practices. On a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being the worst and 4 being the best, technical capacity was assessed with an average of 3, attitudes with an average of 2.4, and ICT skills with an average of 2.1. Pedagogical use was clearly rated the weakest, receiving only an average of 1.7. The result provides an indication of how important it is, with regard to teachers’ training, to pay attention to the fact that teachers themselves should not solely be taught the general use of ICT. Long-term attention must be paid to the introduction and establishment of well-functioning and diverse pedagogical practices in everyday life inside classrooms.

Comparing the answers of different teacher groups, it can be stated that with these indicators, media education is more often implemented by those teachers who work with children in grades 3–6 (children aged 9–12). You can read more about Opeka's reports, such as the differences between different teacher groups and response years, in the Opeka Yearly Report 2020.

Find out more about the work of the Finnish Safer Internet Centre, including its awareness raising, helpline, hotline and youth participation services – or find similar information for Safer Internet Centres throughout Europe.

- media literacy media education education

Related content

- < Previous article

- Next article >