Cyberbullying is growing fast across Europe, but policymakers still lack a shared definition to track and tackle it effectively. A new Joint Research Centre (JRC) science for policy brief analyses existing definitions and various elements of cyberbullying across academic literature and policy documents. Urgent action is needed to better define, monitor and combat the phenomenon.

No common definition, no clear picture

According to the data analysed in the policy brief, cyberbullying has consistently been the top issue flagged to Safer Internet Centre helplines across Europe. In 2024 alone, 14% of the 54,000 calls received were about online bullying. Yet despite its rising prevalence, there is still no EU-wide agreement on what exactly constitutes cyberbullying.

Thirteen Member States have adopted legal definitions, and most rely on general criminal laws that cover harassment, hate speech, or defamation, or civil laws related to education. The lack of a standardised European approach makes it difficult to compare data, assess trends, or measure the impact of anti-bullying programmes. A standard definition and data collection, researchers argue, would allow governments and schools to respond more effectively.

Academic literature on cyberbullying has also grown significantly lately. While research is primarily focused on children and adolescents, studies also focus on specific vulnerable subgroups, among youth and adults, such as migrants or LGBTIQ groups.

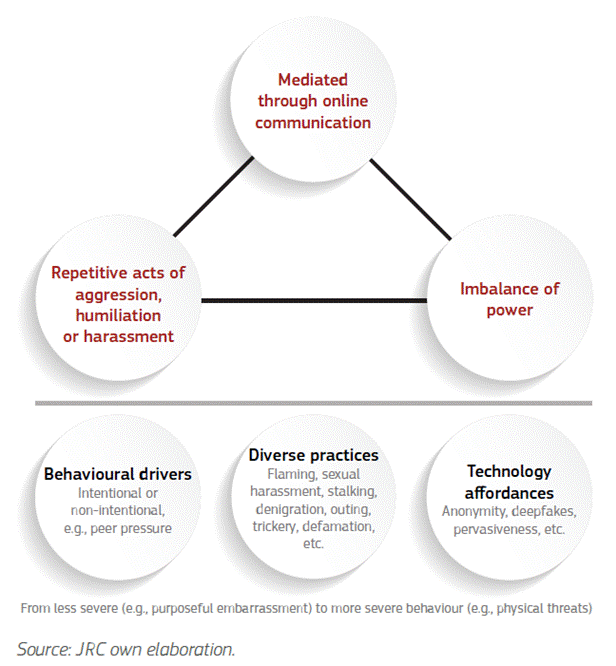

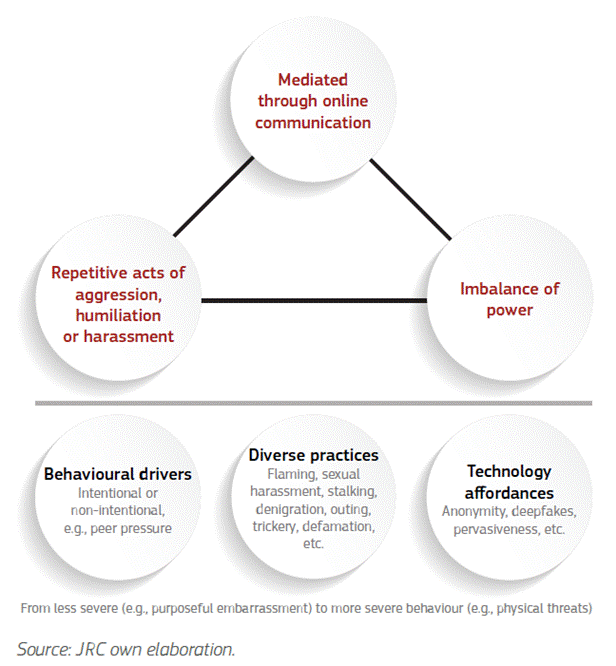

Key elements of cyberbullying

Technology is changing the game

The brief warns that emerging digital technologies are creating unprecedented challenges. Generative AI (artificial intelligence), for instance, is fuelling the rise of deepfakes - manipulated videos that may be designed to humiliate or intimidate victims, including harmful sexualised content. These evolving practices are hard to fit into existing legal frameworks and highlight the need for definitions that keep pace with technological change.

Unlike traditional bullying, online abuse is borderless, persistent and often anonymous. Harmful content can spread instantly, linger indefinitely, and even go viral. Power dynamics are also shifting: while schoolyard bullying might once have relied on physical strength or popularity, online it can hinge on digital skills, access to personal data, or the ability to stay anonymous.

A patchwork of laws and definitions across Europe

The JRC mapped how EU countries address bullying and cyberbullying in their laws. Out of 28 countries analysed (including Norway), almost all have relevant legislation, but only around half provide a clear legal definition. Terms used vary widely - from “cyber violence” to “electronic harassment” - highlighting the difficulties of building a common approach so far.

The lack of consistency is not just a legal issue; it also undermines efforts to protect children and young people, monitor the scale of the problem, and develop targeted responses. “Definitions are often adult-centric, failing to capture the realities of young people’s online lives,” the authors note. They call for children, teenagers and vulnerable groups to be directly involved in shaping future definitions and policies.

EU stepping up action

The report ties to the Action plan against cyberbullying that the European Commission will publish in early 2026. President Ursula von der Leyen has flagged online safety, particularly for minors, as a political priority for her 2024–2029 mandate.

Recent measures - from the Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy to the Digital Services Act (DSA) - already push platforms to act against harmful content. The Council of the EU has recognised the mental health impact of cyberbullying, and the European Parliament has added hate speech to the list of EU crimes.

While this policy brief already provides a comprehensive understanding of the topic, a detailed technical analysis will also be published soon, providing further and deeper insights.

Learn more about the Joint Research Centre of the EC.

Learn more about the Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy on the EC website.

Learn more about the Digital Services Act (DSA) on the EC website.

Learn more about Safer Internet Centres in Europe.

Cyberbullying is growing fast across Europe, but policymakers still lack a shared definition to track and tackle it effectively. A new Joint Research Centre (JRC) science for policy brief analyses existing definitions and various elements of cyberbullying across academic literature and policy documents. Urgent action is needed to better define, monitor and combat the phenomenon.

No common definition, no clear picture

According to the data analysed in the policy brief, cyberbullying has consistently been the top issue flagged to Safer Internet Centre helplines across Europe. In 2024 alone, 14% of the 54,000 calls received were about online bullying. Yet despite its rising prevalence, there is still no EU-wide agreement on what exactly constitutes cyberbullying.

Thirteen Member States have adopted legal definitions, and most rely on general criminal laws that cover harassment, hate speech, or defamation, or civil laws related to education. The lack of a standardised European approach makes it difficult to compare data, assess trends, or measure the impact of anti-bullying programmes. A standard definition and data collection, researchers argue, would allow governments and schools to respond more effectively.

Academic literature on cyberbullying has also grown significantly lately. While research is primarily focused on children and adolescents, studies also focus on specific vulnerable subgroups, among youth and adults, such as migrants or LGBTIQ groups.

Key elements of cyberbullying

Technology is changing the game

The brief warns that emerging digital technologies are creating unprecedented challenges. Generative AI (artificial intelligence), for instance, is fuelling the rise of deepfakes - manipulated videos that may be designed to humiliate or intimidate victims, including harmful sexualised content. These evolving practices are hard to fit into existing legal frameworks and highlight the need for definitions that keep pace with technological change.

Unlike traditional bullying, online abuse is borderless, persistent and often anonymous. Harmful content can spread instantly, linger indefinitely, and even go viral. Power dynamics are also shifting: while schoolyard bullying might once have relied on physical strength or popularity, online it can hinge on digital skills, access to personal data, or the ability to stay anonymous.

A patchwork of laws and definitions across Europe

The JRC mapped how EU countries address bullying and cyberbullying in their laws. Out of 28 countries analysed (including Norway), almost all have relevant legislation, but only around half provide a clear legal definition. Terms used vary widely - from “cyber violence” to “electronic harassment” - highlighting the difficulties of building a common approach so far.

The lack of consistency is not just a legal issue; it also undermines efforts to protect children and young people, monitor the scale of the problem, and develop targeted responses. “Definitions are often adult-centric, failing to capture the realities of young people’s online lives,” the authors note. They call for children, teenagers and vulnerable groups to be directly involved in shaping future definitions and policies.

EU stepping up action

The report ties to the Action plan against cyberbullying that the European Commission will publish in early 2026. President Ursula von der Leyen has flagged online safety, particularly for minors, as a political priority for her 2024–2029 mandate.

Recent measures - from the Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy to the Digital Services Act (DSA) - already push platforms to act against harmful content. The Council of the EU has recognised the mental health impact of cyberbullying, and the European Parliament has added hate speech to the list of EU crimes.

While this policy brief already provides a comprehensive understanding of the topic, a detailed technical analysis will also be published soon, providing further and deeper insights.

Learn more about the Joint Research Centre of the EC.

Learn more about the Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy on the EC website.

Learn more about the Digital Services Act (DSA) on the EC website.

Learn more about Safer Internet Centres in Europe.

- cyberbullying policy

Related content

- < Previous article

- Next article >