Before working through this deep dive, why not take this short quiz to see how much you already know about cyberbullying?

This module will explore the nature of cyberbullying, the impact it can have, and what you need to know about it to support your learners, in terms of education, child protection, and pastoral care. There will also be an opportunity to consider your approach to teaching about online bullying and other hateful or harmful behaviours.

What is cyberbullying?

One of the first challenges faced by any teacher wanting to understand cyberbullying is how to define the nature of this behaviour. The Safer Internet Centre helplines commonly use this working definition:

“Cyberbullying usually involves a child being picked on, ridiculed and intimidated by another child, other children or adults using online technologies. This bullying may involve psychological violence. Cyberbullying can be intentional and unintentional.”

Various academics and researchers have defined cyberbullying differently – some have applied various contexts and factors to their definition, while others have taken definitions of traditional (offline) bullying and applied them to the online space.

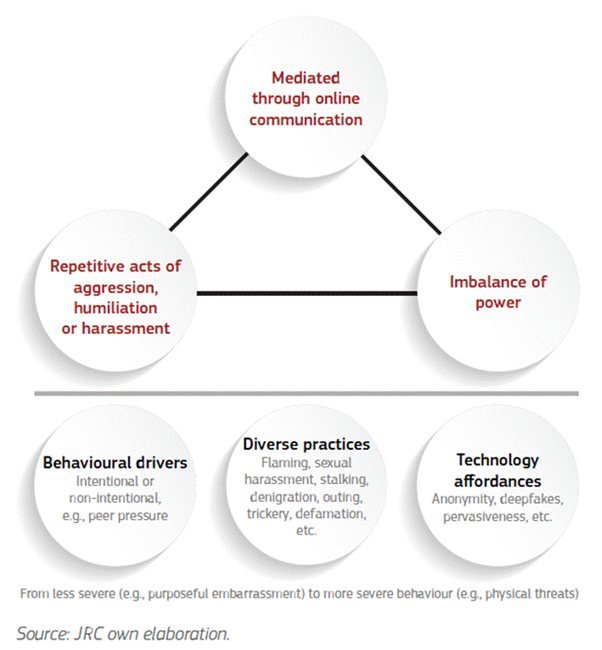

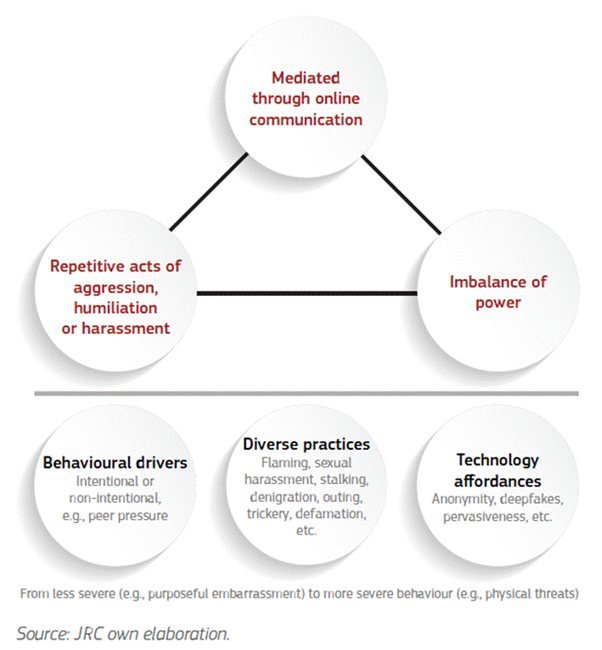

A 2025 Joint Research Centre (JRC) science for policy brief examined existing research and highlighted the following core features of cyberbullying (displayed in Figure 1): mediated through online communication, repetitive acts of aggression/humiliation/harassment and an imbalance of power. These are accompanied by behavioural drivers (motives and intentions, pressure from others), diverse practices (nuanced forms of behaviour, which you will explore in an upcoming section) and technology affordances (how technology can enable certain behaviours such as anonymity, mass sharing of content or creation of deepfakes).

As part of the EU Action plan against cyberbullying, the European Commission is working to prepare a common definition of cyberbullying to help countries across the EU define and fight it.

Activity:

Before continuing, take a moment to think about how you would define cyberbullying. It might be useful to consider it in the context of the children/young people you work with, as well as the factors outlined above.

“Cyberbullying is...”

If you have the opportunity, ask your learners to define cyberbullying. Do their definitions match those of their peers? Do their definitions align with yours? Could you come to an agreed definition with your learners?

What behaviours are recognised as cyberbullying?

Pozza et al (2016) outlined a number of different behaviours that could be considered as forms of cyberbullying:

| Behaviour | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exclusion | the rejection of a person from an online group provoking his/her social marginalisation and exclusion. |

| Online harassment | the repetition of harassment behaviours on the net, including insults, mocking, slander, menacing chain messages, denigrations, name-calling, gossiping, abusive or hate-related behaviours. Harassment differs from nuisance in light of its frequency. It can also be featured as sexual harassment if it includes the spreading of sexual rumours, or the commenting on the body, appearance, sex, or gender of an individual. |

| Griefing | the harassment of someone in a cyber-game or virtual world (e.g. ChatRoulette). |

| Flaming | the online sending of violent or vulgar messages. It differentiates from harassment on the basis that flaming is an online fight featured by anger and violence (e.g. use of capital letter or images to make their point). |

| Trolling | the persistent abusive comments on a website. |

| Cyberstalking | involves continual threatening and sending of rude messages. |

| Cyber-persecution | continuous and repetitive harassment, denigration, insulting, and threats. |

| Masquerade | a situation where a bully creates a fake identity to harass someone else. |

| Impersonation | the impersonation of someone else to send malicious messages, as well as the breaking into someone's account to send messages, or like posts that will cause embarassment or damage to the person's reputation and affect his/her social life. |

| Fraping | the changing of details on someone's Facebook page when they leave it open (e.g. changing his political views into Nazi supporter). |

| Catfishing | occurs when someone steals your child's online identity to recreate social networking profiles for deceptive purposes. |

| Outing | occurs when personal and private information, pictures, or videos about someone are shared publicly without permission. |

| Dissing | occurs when someone uploads cruel information, photos or videos of children online. |

| Tricking | occurs when someone tricks someone else into revealing secrets or embasrasing information, which is then shared online. |

| Grooming | befriending and establishing an emotional connection with a child, and sometimes the family, to lower the child's inhbitions for child sexual abuse. |

| Sexting | the circulation of sexualised images via mobile phones or the internet without a person's consent. |

| Sexcasting | is similar to sexting but it involves high definition videos of sexually explicit content. |

| Happy slapping | aggressive or degrading behaviour conducted and recorded by a bystander and the video is then forwarded to other people's phones or posted on a website. |

| Threats | to damage existing relationships, threats to family, threats to home environment, threat of physical violence, death threats. |

Table 1: Behaviours that may be considered cyberbullying, Pozza et al (2016)

Take a moment to consider which of these behaviours might be common or possible among the groups of children/young people you work with. Keep in mind that your students might use games, apps and online services that allow them to interact with users older than themselves, so some of these behaviours might be present or possible in those online spaces.

The behaviours listed above are from research conducted in 2016. What other cyberbullying behaviours have emerged since then, and how do you think recent technology advances (such as AI (artificial intelligence)) have affected cyberbullying?

How common is cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying (and bullying in general) is not a new phenomenon, but it is sadly a persistent risk that can be faced by online users (both children and adults).

Research studies report a wide range of prevalence of cyberbullying among youth and different studies may give very different numbers based on a number of factors such as sample size and type, methodology, and how cyberbullying is measured or defined.

A meta-analysis of cyberbullying studies in EU countries in 2022 found the following:

- Cybervictimisation – young people reporting being a victim of cyberbullying ranged from 3%-31%.

- Cyberperpetration – young people reporting they have bullied others ranged from 3%-30%.

- Cyberbystander – young people reporting they had seen cyberbullying happening to others ranged from 13%-53%.

Although figures vary from study to study, all research and statistics point to cyberbullying as a serious issue that can affect children and young people.

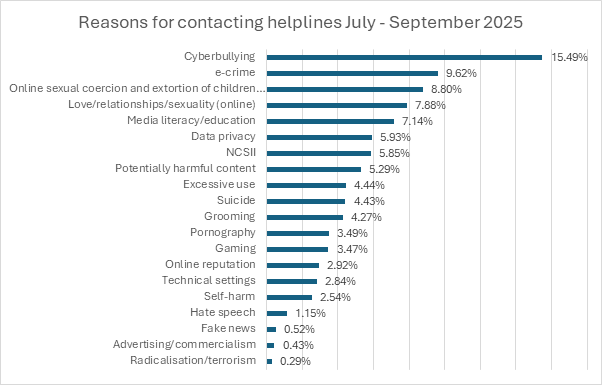

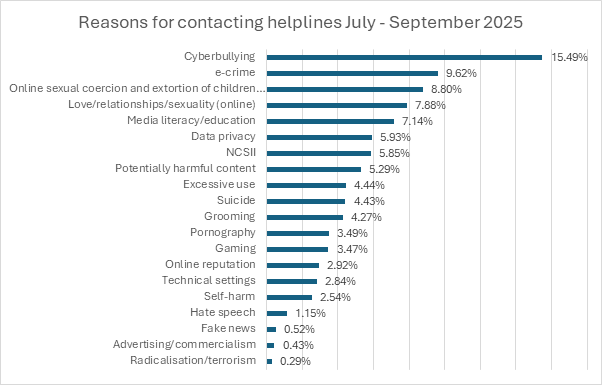

The Insafe network of Safer Internet Centres operates helplines for educators, youth, parents, and caregivers seeking help and advice on online safety concerns. In 2024, 14% of contacts with the helplines were regarding cyberbullying issues. Figure 2 shows an example of the different reasons for contacting the helplines over a three-month period.

Table description: Among the most common reasons for contacting helplines between July and September 2025 were cyberbullying, e-crime, and online sexual coercion and child extortion. Followed by, in descending order, love/relationships/sexuality (online), media literacy/education, data privacy, NCSII (non-consensual sharing of intimate images), potentially harmful content, excessive use, suicide, grooming, pornography, gaming, online reputation, technical settings, self-harm, hate speech, fake news, advertising/commercialism, radicalisation/terrorism.

Since 2019, cyberbullying has consistently been the most common reason for contacting the helplines in every quarterly review of reasons for contact.

Why do people cyberbully?

There are a number of different reasons why someone (child or adult) may choose to bully someone else online.

These include:

- An extension of bullying offline – shifting the behaviour online allows a bully to target someone at any time of day or night, and from any geographical location. It also allows them to abuse or harass someone multiple times very quickly, whether through repeated behaviour on one app or platform, or a wide-ranging attack across multiple online platforms and services.

- Seeking ‘revenge’ on someone who they believed has wronged them.

- Treating someone else badly in order to make the bully feel ‘better’ about themselves.

- Displacement – some bullies are the victim of bullying themselves and seek to displace their feelings about their own abuse by targeting someone else with the same behaviour.

- Perceiving bullying to be ‘fun’ or a game; being online (and sometimes anonymous) can disinhibit people to see cyberbullying behaviour as ‘not real’.

- A lack of engagement in, or understanding of, morals, emotions and empathy.

- Joining in with the bullying behaviour by others in order to conform to social norms or ‘fit in’.

- An attempt to get attention from other users.

- A targeted attack on an individual or a group motivated by dislike or hatred for personal characteristics (such as race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.). In these cases, bullying would also be considered hate speech and (if inciting violence) possibly also a hate crime. The EU Action plan against cyberbullying provides a specific focus on groups, such as LGBTIQ and migrants, that may be vulnerable to this type of bullying.

What do my learners need to know about cyberbullying?

It is important to discuss with children and young people about the nature of cyberbullying, the impact it can have, and the ways in which it can be prevented and responded to, by individuals, communities, organisations and society.

One approach to educating students about cyberbullying is to focus on these themes and questions under these three key areas:

- Understanding cyberbullying – What is cyberbullying? How does it make people feel? Why and how do people bully? Is cyberbullying against the law?

- Preventing cyberbullying – What is positive and respectful communication online? What is the role of privacy? What is the difference between bullying and ‘banter’? How do we manage online conflict and disagreement? What are the positive norms we want in our digital lives? What is the role of the school in preventing cyberbullying?

- Responding to cyberbullying – How can someone get help online? What tools are there to help users? How do we encourage people to intervene or to seek help? How do we resolve a cyberbullying issue? What is the role of the school in responding to cyberbullying?

An analysis of cyberbullying prevention programmes by Hajnal (2021) found that programmes that focused on online safety education were more effective in encouraging youth to report cyberbullying and seek help, whereas Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programmes were more effective in reducing the perpetration of cyberbullying among youth. This is something to consider in your own practice – does your approach to teaching about cyberbullying focus on online safety, SEL, or both?

One educational resource that supports both online safety and SEL education on cyberbullying is the KID_ACTIONS Educational toolkit, which provides activities for teachers to run with learners aged 11+, tied to the key themes outlined above. Many activities are suitable for younger children with some adaptation. There are also guidance documents for educators on how to tackle this area.

What advice should I give my learners about dealing with cyberbullying?

A key part of educating youth about cyberbullying is to help them develop and use strategies for managing tricky situations online, and to know how to get help when things go wrong. The following is useful advice for your students about what to do if they or someone they know is being cyberbullied:

- Tell someone – reaching out to a trusted adult (such as a parent/caregiver or teacher) is crucial to ensure that a young person gets the help and support they need to tackle a cyberbullying issue. In many European countries, young people can also call 116 111 to receive support from a helpline. Alternatively, they (or you) can contact your national Safer Internet Centre. Find further information on helpline services here.

- Don’t retaliate – it can be tempting for children and young people to treat a bully in the same way that they are being treated – to be abusive and hurtful back. However, this usually makes the situation worse and can lead to them also being labelled as a bully when they were acting in self-defence.

- Save the evidence – using screenshots and video capture tools to save proof of a bully’s actions is an important step. This can ensure that evidence can be passed to a trusted adult, law enforcement (if laws have been broken) and online services in order to take informed action against a bully’s behaviour.

- Use online tools – tools such as blocking and reporting can prevent a bully from contacting their intended target, and alert online services that a user is in breach of the rules or community standards. Using other tools, such as privacy settings, can empower users to manage their personal information and interactions with other users.

- What are the laws? – only around half of EU Member States have defined cyberbullying in their legislation, meaning that there may or may not be specific cyberbullying laws in your country. Many behaviours in cyberbullying may fall under other laws (such as harassment, stalking, non-consensual intimate image (NCII) abuse , deepfakes or hate speech). Helping your learners to understand the laws around online behaviour can empower them to recognise and report it. Want to know what the legislation is in your country? Check out this JRC policy report on cyberbullying legislation across the EU.

What else can I do?

Many cyberbullying incidents take place away from school but directly affect the safety and well-being of your learners. In order to help and support them, consider the following:

- What is my school’s approach to tackling bullying?

Take time to make yourself familiar with your school’s policies and procedures for managing bullying incidents, particularly procedures for handling disclosures – a learner reporting cyberbullying to you should always be taken seriously. Be sure you are aware of any anti-bullying educational programmes or schemes that are used with learners in your school, and check out the next section for useful educational resources. - What are my own views on cyberbullying?

No two cyberbullying incidents are the same, and it is important to keep an open mind and a non-judgmental approach when educating about cyberbullying or responding to issues. Individual differences and context play a huge role in how young people may be targeted and involved in cyberbullying, as do other factors such as sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, and gender. Did you know that research shows boys are more likely than girls (14% versus 9%) to cyberbully someone? - Where can I get help?

Ensure you know who to contact at school to support any learners involved in cyberbullying incidents (as targets or perpetrators). Identify other sources of help, such as local law enforcement, your national Safer Internet Centre helpline, and other organisations/professionals that might provide further assistance. - How can I stay up to date?

The BIK bulletin, a quarterly newsletter, provides regular updates on online safety, including developments in tackling cyberbullying as they emerge. The Digital Services Act (DSA) mandates popular platforms to respond to cyberbullying of minors more promptly and clearly – you can learn more about how the DSA is working to protect children online in this family-friendly booklet. It is available to download in all EU languages, and Norwegian. - What can I do in the classroom to promote positive and respectful behaviour?

It can be tempting to only teach about online issues when something has gone wrong, but a proactive approach to online safety education is key. Taking time to help your learners explore and recognise the importance of positive and respectful communication and healthy relationships can help prevent issues from ever occurring and also empower them to seek help if problems do arise.

Further information and resources

Want to learn more or educate your learners about cyberbullying? These resources may be useful:

- EU Action plan against cyberbullying

The action plan presents a common definition of cyberbullying and information on how EU Member States are working to tackle cyberbullying. The action plan has a focus on minors and on vulnerable groups of young people (up to 29 years old), such as people with disabilities, LGBTIQ, migrants and members of religious, racial or ethnic minorities. - ‘Child Online Safety: What Educators need to know’ MOOC

This massive open online course ran in 2025 but is archived and available for free for any educator to work through. Module 2 provides an in-depth look at understanding, preventing, and responding to cyberbullying as an educator, as well as steps you can take to promote an inclusive and supportive learning environment for discussing sensitive issues such as cyberbullying. - Better Internet for Kids resources

Educational resources from across the Insafe network of Safer Internet Centres. You can search for ‘cyberbullying’ for resources in your language and for resources for different age groups. - KID_ACTIONS

Information, research and educational materials for educators to work with their students on preventing, understanding and responding to cyberbullying. - Safer Internet Centres

Safer Internet Centres across Europe provide a wealth of content and services to support children and young people, and those that care for them: parents and carers; teachers, educators and other professionals; and other stakeholders.

Before working through this deep dive, why not take this short quiz to see how much you already know about cyberbullying?

This module will explore the nature of cyberbullying, the impact it can have, and what you need to know about it to support your learners, in terms of education, child protection, and pastoral care. There will also be an opportunity to consider your approach to teaching about online bullying and other hateful or harmful behaviours.

What is cyberbullying?

One of the first challenges faced by any teacher wanting to understand cyberbullying is how to define the nature of this behaviour. The Safer Internet Centre helplines commonly use this working definition:

“Cyberbullying usually involves a child being picked on, ridiculed and intimidated by another child, other children or adults using online technologies. This bullying may involve psychological violence. Cyberbullying can be intentional and unintentional.”

Various academics and researchers have defined cyberbullying differently – some have applied various contexts and factors to their definition, while others have taken definitions of traditional (offline) bullying and applied them to the online space.

A 2025 Joint Research Centre (JRC) science for policy brief examined existing research and highlighted the following core features of cyberbullying (displayed in Figure 1): mediated through online communication, repetitive acts of aggression/humiliation/harassment and an imbalance of power. These are accompanied by behavioural drivers (motives and intentions, pressure from others), diverse practices (nuanced forms of behaviour, which you will explore in an upcoming section) and technology affordances (how technology can enable certain behaviours such as anonymity, mass sharing of content or creation of deepfakes).

As part of the EU Action plan against cyberbullying, the European Commission is working to prepare a common definition of cyberbullying to help countries across the EU define and fight it.

Activity:

Before continuing, take a moment to think about how you would define cyberbullying. It might be useful to consider it in the context of the children/young people you work with, as well as the factors outlined above.

“Cyberbullying is...”

If you have the opportunity, ask your learners to define cyberbullying. Do their definitions match those of their peers? Do their definitions align with yours? Could you come to an agreed definition with your learners?

What behaviours are recognised as cyberbullying?

Pozza et al (2016) outlined a number of different behaviours that could be considered as forms of cyberbullying:

| Behaviour | Definition |

|---|---|

| Exclusion | the rejection of a person from an online group provoking his/her social marginalisation and exclusion. |

| Online harassment | the repetition of harassment behaviours on the net, including insults, mocking, slander, menacing chain messages, denigrations, name-calling, gossiping, abusive or hate-related behaviours. Harassment differs from nuisance in light of its frequency. It can also be featured as sexual harassment if it includes the spreading of sexual rumours, or the commenting on the body, appearance, sex, or gender of an individual. |

| Griefing | the harassment of someone in a cyber-game or virtual world (e.g. ChatRoulette). |

| Flaming | the online sending of violent or vulgar messages. It differentiates from harassment on the basis that flaming is an online fight featured by anger and violence (e.g. use of capital letter or images to make their point). |

| Trolling | the persistent abusive comments on a website. |

| Cyberstalking | involves continual threatening and sending of rude messages. |

| Cyber-persecution | continuous and repetitive harassment, denigration, insulting, and threats. |

| Masquerade | a situation where a bully creates a fake identity to harass someone else. |

| Impersonation | the impersonation of someone else to send malicious messages, as well as the breaking into someone's account to send messages, or like posts that will cause embarassment or damage to the person's reputation and affect his/her social life. |

| Fraping | the changing of details on someone's Facebook page when they leave it open (e.g. changing his political views into Nazi supporter). |

| Catfishing | occurs when someone steals your child's online identity to recreate social networking profiles for deceptive purposes. |

| Outing | occurs when personal and private information, pictures, or videos about someone are shared publicly without permission. |

| Dissing | occurs when someone uploads cruel information, photos or videos of children online. |

| Tricking | occurs when someone tricks someone else into revealing secrets or embasrasing information, which is then shared online. |

| Grooming | befriending and establishing an emotional connection with a child, and sometimes the family, to lower the child's inhbitions for child sexual abuse. |

| Sexting | the circulation of sexualised images via mobile phones or the internet without a person's consent. |

| Sexcasting | is similar to sexting but it involves high definition videos of sexually explicit content. |

| Happy slapping | aggressive or degrading behaviour conducted and recorded by a bystander and the video is then forwarded to other people's phones or posted on a website. |

| Threats | to damage existing relationships, threats to family, threats to home environment, threat of physical violence, death threats. |

Table 1: Behaviours that may be considered cyberbullying, Pozza et al (2016)

Take a moment to consider which of these behaviours might be common or possible among the groups of children/young people you work with. Keep in mind that your students might use games, apps and online services that allow them to interact with users older than themselves, so some of these behaviours might be present or possible in those online spaces.

The behaviours listed above are from research conducted in 2016. What other cyberbullying behaviours have emerged since then, and how do you think recent technology advances (such as AI (artificial intelligence)) have affected cyberbullying?

How common is cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying (and bullying in general) is not a new phenomenon, but it is sadly a persistent risk that can be faced by online users (both children and adults).

Research studies report a wide range of prevalence of cyberbullying among youth and different studies may give very different numbers based on a number of factors such as sample size and type, methodology, and how cyberbullying is measured or defined.

A meta-analysis of cyberbullying studies in EU countries in 2022 found the following:

- Cybervictimisation – young people reporting being a victim of cyberbullying ranged from 3%-31%.

- Cyberperpetration – young people reporting they have bullied others ranged from 3%-30%.

- Cyberbystander – young people reporting they had seen cyberbullying happening to others ranged from 13%-53%.

Although figures vary from study to study, all research and statistics point to cyberbullying as a serious issue that can affect children and young people.

The Insafe network of Safer Internet Centres operates helplines for educators, youth, parents, and caregivers seeking help and advice on online safety concerns. In 2024, 14% of contacts with the helplines were regarding cyberbullying issues. Figure 2 shows an example of the different reasons for contacting the helplines over a three-month period.

Table description: Among the most common reasons for contacting helplines between July and September 2025 were cyberbullying, e-crime, and online sexual coercion and child extortion. Followed by, in descending order, love/relationships/sexuality (online), media literacy/education, data privacy, NCSII (non-consensual sharing of intimate images), potentially harmful content, excessive use, suicide, grooming, pornography, gaming, online reputation, technical settings, self-harm, hate speech, fake news, advertising/commercialism, radicalisation/terrorism.

Since 2019, cyberbullying has consistently been the most common reason for contacting the helplines in every quarterly review of reasons for contact.

Why do people cyberbully?

There are a number of different reasons why someone (child or adult) may choose to bully someone else online.

These include:

- An extension of bullying offline – shifting the behaviour online allows a bully to target someone at any time of day or night, and from any geographical location. It also allows them to abuse or harass someone multiple times very quickly, whether through repeated behaviour on one app or platform, or a wide-ranging attack across multiple online platforms and services.

- Seeking ‘revenge’ on someone who they believed has wronged them.

- Treating someone else badly in order to make the bully feel ‘better’ about themselves.

- Displacement – some bullies are the victim of bullying themselves and seek to displace their feelings about their own abuse by targeting someone else with the same behaviour.

- Perceiving bullying to be ‘fun’ or a game; being online (and sometimes anonymous) can disinhibit people to see cyberbullying behaviour as ‘not real’.

- A lack of engagement in, or understanding of, morals, emotions and empathy.

- Joining in with the bullying behaviour by others in order to conform to social norms or ‘fit in’.

- An attempt to get attention from other users.

- A targeted attack on an individual or a group motivated by dislike or hatred for personal characteristics (such as race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.). In these cases, bullying would also be considered hate speech and (if inciting violence) possibly also a hate crime. The EU Action plan against cyberbullying provides a specific focus on groups, such as LGBTIQ and migrants, that may be vulnerable to this type of bullying.

What do my learners need to know about cyberbullying?

It is important to discuss with children and young people about the nature of cyberbullying, the impact it can have, and the ways in which it can be prevented and responded to, by individuals, communities, organisations and society.

One approach to educating students about cyberbullying is to focus on these themes and questions under these three key areas:

- Understanding cyberbullying – What is cyberbullying? How does it make people feel? Why and how do people bully? Is cyberbullying against the law?

- Preventing cyberbullying – What is positive and respectful communication online? What is the role of privacy? What is the difference between bullying and ‘banter’? How do we manage online conflict and disagreement? What are the positive norms we want in our digital lives? What is the role of the school in preventing cyberbullying?

- Responding to cyberbullying – How can someone get help online? What tools are there to help users? How do we encourage people to intervene or to seek help? How do we resolve a cyberbullying issue? What is the role of the school in responding to cyberbullying?

An analysis of cyberbullying prevention programmes by Hajnal (2021) found that programmes that focused on online safety education were more effective in encouraging youth to report cyberbullying and seek help, whereas Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programmes were more effective in reducing the perpetration of cyberbullying among youth. This is something to consider in your own practice – does your approach to teaching about cyberbullying focus on online safety, SEL, or both?

One educational resource that supports both online safety and SEL education on cyberbullying is the KID_ACTIONS Educational toolkit, which provides activities for teachers to run with learners aged 11+, tied to the key themes outlined above. Many activities are suitable for younger children with some adaptation. There are also guidance documents for educators on how to tackle this area.

What advice should I give my learners about dealing with cyberbullying?

A key part of educating youth about cyberbullying is to help them develop and use strategies for managing tricky situations online, and to know how to get help when things go wrong. The following is useful advice for your students about what to do if they or someone they know is being cyberbullied:

- Tell someone – reaching out to a trusted adult (such as a parent/caregiver or teacher) is crucial to ensure that a young person gets the help and support they need to tackle a cyberbullying issue. In many European countries, young people can also call 116 111 to receive support from a helpline. Alternatively, they (or you) can contact your national Safer Internet Centre. Find further information on helpline services here.

- Don’t retaliate – it can be tempting for children and young people to treat a bully in the same way that they are being treated – to be abusive and hurtful back. However, this usually makes the situation worse and can lead to them also being labelled as a bully when they were acting in self-defence.

- Save the evidence – using screenshots and video capture tools to save proof of a bully’s actions is an important step. This can ensure that evidence can be passed to a trusted adult, law enforcement (if laws have been broken) and online services in order to take informed action against a bully’s behaviour.

- Use online tools – tools such as blocking and reporting can prevent a bully from contacting their intended target, and alert online services that a user is in breach of the rules or community standards. Using other tools, such as privacy settings, can empower users to manage their personal information and interactions with other users.

- What are the laws? – only around half of EU Member States have defined cyberbullying in their legislation, meaning that there may or may not be specific cyberbullying laws in your country. Many behaviours in cyberbullying may fall under other laws (such as harassment, stalking, non-consensual intimate image (NCII) abuse , deepfakes or hate speech). Helping your learners to understand the laws around online behaviour can empower them to recognise and report it. Want to know what the legislation is in your country? Check out this JRC policy report on cyberbullying legislation across the EU.

What else can I do?

Many cyberbullying incidents take place away from school but directly affect the safety and well-being of your learners. In order to help and support them, consider the following:

- What is my school’s approach to tackling bullying?

Take time to make yourself familiar with your school’s policies and procedures for managing bullying incidents, particularly procedures for handling disclosures – a learner reporting cyberbullying to you should always be taken seriously. Be sure you are aware of any anti-bullying educational programmes or schemes that are used with learners in your school, and check out the next section for useful educational resources. - What are my own views on cyberbullying?

No two cyberbullying incidents are the same, and it is important to keep an open mind and a non-judgmental approach when educating about cyberbullying or responding to issues. Individual differences and context play a huge role in how young people may be targeted and involved in cyberbullying, as do other factors such as sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, and gender. Did you know that research shows boys are more likely than girls (14% versus 9%) to cyberbully someone? - Where can I get help?

Ensure you know who to contact at school to support any learners involved in cyberbullying incidents (as targets or perpetrators). Identify other sources of help, such as local law enforcement, your national Safer Internet Centre helpline, and other organisations/professionals that might provide further assistance. - How can I stay up to date?

The BIK bulletin, a quarterly newsletter, provides regular updates on online safety, including developments in tackling cyberbullying as they emerge. The Digital Services Act (DSA) mandates popular platforms to respond to cyberbullying of minors more promptly and clearly – you can learn more about how the DSA is working to protect children online in this family-friendly booklet. It is available to download in all EU languages, and Norwegian. - What can I do in the classroom to promote positive and respectful behaviour?

It can be tempting to only teach about online issues when something has gone wrong, but a proactive approach to online safety education is key. Taking time to help your learners explore and recognise the importance of positive and respectful communication and healthy relationships can help prevent issues from ever occurring and also empower them to seek help if problems do arise.

Further information and resources

Want to learn more or educate your learners about cyberbullying? These resources may be useful:

- EU Action plan against cyberbullying

The action plan presents a common definition of cyberbullying and information on how EU Member States are working to tackle cyberbullying. The action plan has a focus on minors and on vulnerable groups of young people (up to 29 years old), such as people with disabilities, LGBTIQ, migrants and members of religious, racial or ethnic minorities. - ‘Child Online Safety: What Educators need to know’ MOOC

This massive open online course ran in 2025 but is archived and available for free for any educator to work through. Module 2 provides an in-depth look at understanding, preventing, and responding to cyberbullying as an educator, as well as steps you can take to promote an inclusive and supportive learning environment for discussing sensitive issues such as cyberbullying. - Better Internet for Kids resources

Educational resources from across the Insafe network of Safer Internet Centres. You can search for ‘cyberbullying’ for resources in your language and for resources for different age groups. - KID_ACTIONS

Information, research and educational materials for educators to work with their students on preventing, understanding and responding to cyberbullying. - Safer Internet Centres

Safer Internet Centres across Europe provide a wealth of content and services to support children and young people, and those that care for them: parents and carers; teachers, educators and other professionals; and other stakeholders.